My previous post on Claudia Goldin’s Career and Family has a reading time of 10 minutes, according to the Substack counter. Not wanting to make the post any longer, and preferring to focus on the major themes of the work, I did not go into certain details.

Here is some material that I left out of my previous post.

The value of homemaking

In the course of her historical overview, Goldin takes a look at how unpaid domestic labor is counted, or not, in econometric data. Goldin looks at the work of economists Margaret Reid and Simon Kuznets in this area (Ch. 3).

Goldin crossed paths with Margaret Reid on Columbia’s campus when Reid was an emerita and Goldin was a grad student; Goldin chides herself for not getting to know Reid better. Kuznets, who won the Nobel Prize in 1971, was the thesis advisor of Goldin’s thesis advisor: she says “I proudly claim him as my intellectual grandfather”.

In 1934, Reid’s doctoral dissertation, Economics of Household Production,

[…] was among the first to assess the value of unpaid work in the household and to analyze how married women chose between working in the home and working outside their own homes for pay. […]

Margaret’s study aimed to put women’s unpaid work into calculations of national income.

In the early years of the Great Depression, Simon Kuznets was tasked with devising measures that Congress could use to assess the economic decline, and by the Department of Commerce to come up with a general system of econometric analysis. Several of his measures, such as GDP, are still used today.

At the very moment that Reid was espousing the inclusion of women’s unpaid labor in estimates of a nation’s income, Kuznets was formulating his version of these esoteric, yet critically important, concepts. […]

[…] Kuznets agonized over whether to include labor of unpaid household workers and caregivers in official statistics. He ultimately decided not to.

Kuznets believed that there was “no reliable basis for estimating their value.” Reid disagreed, and proposed methods for doing so. Goldin says that “advocacy groups and others” have done such estimates (using Reid’s methods?) and the latest figures put the value at 20% of GNP.

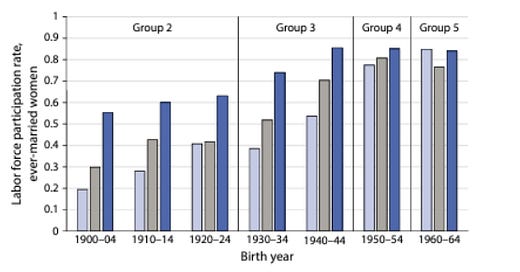

These figures raise a question: if domestic labor is so valuable, why should we push both parents to work 40+ hours outside the home while they have school-aged children? Maybe the women of Goldin’s Group 3 had the right idea: family, then work. Goldin characterizes it as “family then job”, declining to apply her honorific, “career”, to these women’s work. This was surely false for some of them. The retired NPR host Diane Rehm is of this generation; she definitely had a career. I heard her say more than once on her program, “You can have it all, just not at the same time.” She did not go to college, though; her path was jobs then family then career. (But of course, that was another time. I’ve outlined solution more appropriate for our time in 1200 Hours.)

Which segues into another topic:

Narrow norms

From the 1950s to 1972, the median college-graduate woman married before the age of twenty-three. To my students today, that is shocking, even terrifying. (Goldin, p116)

“Shocking, even terrifying”? The median age at first marriage for American women has been below age 23 for most of US history. Looking beyond the US, across cultures and throughout recorded history, it has not been unusual for women to be married by age 23.

Maybe we should take a harder look at the prevailing norms of the professional-managerial class. Not everyone needs to follow the same path. I personally know two women with PhDs and tenure who are over 45 and have been with the same man since high school, though they didn’t formally wed until the women were in grad school. I’ve known other women who had children before age 23; when those women were in their late 30s, their children were independent or nearly so. The women were free to explore new paths (advanced degrees, career changes, travel, second marriages, etc.) while they were still in the broad prime of life, and they did not suffer the disappointments of the many women in Goldin’s Group 4 who waited too long to start families.

Goldin shares that she is married but has no children. I don’t want to make too much of this. It has no bearing on the quality of her descriptive data, but I think it is fair to ask whether her perspective has colored her normative conclusions.

Are corporations more progressive than small businesses?

In her comparison of lawyers and pharmacists, Goldin says that decades ago pharmacists worked long and irregular hours much as lawyers did, but no longer do.

What changed in pharmacies? Drugstores became big business, increasing both in size and in scope of operations across the twentieth century. From the 1950s to today the fraction of independent pharmacies plummeted, and with that transformation, the fraction of pharmacists working in independent practices dropped drastically too. Changes in our health care and health insurance systems reinforced these trends and produced an increase in the share of pharmacists working in hospitals and mail-order pharmacies.

Each of these shifts reduced the number of self-employed pharmacists and increased the fraction working as employees of corporations. Whereas the corporate sector isn’t generally viewed as an agent of progressive change, in this case it played exactly that role. The shift of pharmacies to the corporate sector meant that ownership was no longer relevant to a pharmacist’s job. Since men had been the owners and women were primarily their assistants, the shift meant that men and women could be more equal as pharmacists. The person receiving the net profits from the enterprise was no longer the male pharmacist. It was the stockholders. (pp187-188, emphasis added)

Also during this period, health care costs became prohibitively expensive for many people, driven in large part by the rise in prescription drug prices. The absorption of small businesses by large corporate chains such as Wal-Mart or Home Depot has been detrimental to many communities. Reducing independent proprietors to corporate employees is not what I would call progressive. In the larger picture, Big Pharma has not been an agent of progressive change, even if its takeover of drug retailing nearly eliminated the gender gap in pharmacists’ earnings as an incidental side effect.

That’s all for now. I may add more later.