Contrasting the epistemologies of Plato, Aristotle, and the Sophists, Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg state,

The scholarly tradition depicts Plato and Aristotle alone as concerned with truth, meaning absolute truth that can be demonstrated by empirical evidence or insight into divinely instilled ideals. . . . The Sophists believed that only provisional or probable knowledge was available to human beings. (The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, 22)

This strikes me as an oversimplification, for it seems to reduce three distinct positions to two.

1. Overview of the three positions

On the issue of knowledge of the contingent (i.e., that which is not necessary — that which could have been otherwise), the positions of the Sophists, Plato, and Aristotle, are, roughly speaking, as follows:

• All knowledge is knowledge of the contingent (the Sophists)

• No knowledge is knowledge of the contingent (Plato)

• Some knowledge is knowledge of the contingent (Aristotle)

To put it another way, the issue of knowledge of the contingent can be expressed in two questions: (1) the question of whether beliefs that are probably true, but not necessarily true, can be construed as knowledge, and (2) the question of whether beliefs that are true relative to certain circumstances, but not all possible circumstances, can be construed as knowledge. To the first question, Plato and Aristotle both answer in the negative, while the Sophists answer in the affirmative. To the latter question, Plato answers in the negative, while both Aristotle and the Sophists answer in the affirmative (but Aristotle’s affirmation is strictly qualified).

The above characterization of the Sophists is based on Bizzell & Herzberg’s work (22-24) and on George Kennedy’s Classical Rhetoric and its Christian and Secular Tradition (ch. 3). I will examine the positions of Plato and Aristotle in more detail.

2. Plato’s position

Plato believed that only that which was fully real was fully knowable, so before I discuss Plato’s epistemology I must explain certain key aspects of his metaphysics.

Plato’s metaphysics

For Plato, reality is a matter of degree. There is a continuum, ranging from the completely unreal to the completely real. This continuum can be divided into two main categories: the world of being and the world of becoming (a distinction which Plato inherited from earlier Greek philosophers). That which belongs to the world of being is simple, eternal, unchanging, absolute, and unique. That which belongs to the world of becoming is composite, temporal, mutable, relative, and multiple. Plato claims that that which is completely real must belong to the world of being, and can be grasped only by the intellect, while that which belongs to the world of becoming is mere appearance, and is grasped by the senses.

The only completely real things are what Plato calls the Forms. The Forms are what make things what they are. For example, what makes beautiful things beautiful is that they "partake of the character" of the Form of Beauty, that is, of Beauty itself. In other words, Beauty itself is something separate from the various beautiful things we see in the sensible world. These visible things are beautiful only insofar as they embody Beauty.

Many people would say that "Beauty" is just an abstraction, and that the things that are truly real are the beautiful things we experience physically. Plato's view is exactly the opposite: the Forms of Beauty, Humanity, Justice, etc., are fully real, but this beautiful flower or that woman or some particular just judgement are only real in a limited sense, for these things are like mere shadows or reflections of the Forms they represent.

This means that the objects of the sensible world are dependent on the Forms for their existence, but not vice versa, for a thing can exist without a shadow or a reflection, but a shadow or a reflection must be a shadow or a reflection of something else. At the pinnacle of reality is the Form of the Good--Goodness itself. The Good is the source of reality, on which everything else depends for its existence.

Plato’s epistemology

Many modern philosophers view knowledge as a species of belief--beliefs that are justified and true are knowledge. According to Plato, however, knowledge and belief (or opinion) are completely separate faculties with completely separate objects. We can have knowledge about the intelligible world only; about the sensible world we can have beliefs, which may be true or false, but we cannot have knowledge. Plato's view is that, strictly speaking, to know something means to have a permanent, infallible understanding of it. But the world of becoming is constantly changing, so no such understanding of it is possible. Only the unchanging Forms can be truly known. So to know something means to have a permanent, infallible understanding of the true nature of a Form.

Plato explains what he means in greater detail in Book VI of the Republic. Our minds interact with reality by way of four categorically distinct powers or faculties. Two of these powers deal with aspects of the changing world of becoming and two deal with the unchanging world of being. They are ranked according to the degree of reality of their objects, which is also the degree to which propositions derived from that power can be classified as true or false in an unqualified sense.

From the lowest to the highest, these powers are: imagination/perception, belief, thought, and knowledge.

At the lowest level is imagination and perception, which Plato apparently lumps together into a single image-generating faculty that gives us our immediate experiences of sights, sounds, etc.

Next comes the power of belief, which uses inductive reasoning to give us our common-sense understanding of everyday events and objects. This faculty allows a person to tell when different perceptions refer to the same object, or when similar perceptions refer to different objects. For example, this is what tells a mother that her child remains the same person from birth to adulthood, even though the child's appearance changes.

Next comes the power of thought, i.e., deductive reasoning, which infers apodeictically certain conclusions from the first principles of the sciences, without questioning those principles themselves. These first principles or axioms may be characterized as hypotheses about Forms, e.g., the axioms of geometry may be viewed as hypotheses about the Form of Space). These deductions are necessarily true, but they fall short of being called knowledge in the strictest sense of the word because they are hypothetical (if the axioms of geometry correctly describe space, then the theorems necessarily follow).

Finally there is the faculty of understanding, which achieves knowledge through dialectic. Dialectical inquiry, which Plato illustrates in his Socratic dialogues, questions the first principles of the sciences and seeks to eliminate any hidden contradictions among these axioms, taking nothing for granted. Dialectic thereby arrives at adequate conceptual definitions of the Forms, which constitute knowledge.

Dialectic is not simply a matter of arriving at a consensus. Knowledge of the eternal Forms is possible because that which knows, i.e., the soul, is itself immortal, and has been exposed to the Forms prior to being connected to a physical body. When dialectic uncovers the true nature of a Form, the soul recognizes this based on its past acquaintance with the Form. Thus, gaining knowledge of the forms is actually a kind of recollection. The ultimate goal of this process is to gain an understanding of the Form of the Good. When the Good is understood, an understanding of everything else will follow.

Thus, we have understanding of Forms, thoughts about hypotheses about Forms, beliefs about material embodiments of Forms, and perceptions of images of material embodiments of Forms.

3. Aristotle’s position

The major difference between Plato and Aristotle on the question of knowledge is that Aristotle does not limit knowledge to the realm of being. Aristotle considers the realm of becoming to be the object of knowledge, also–and not merely derivatively, as an imperfect manifestation of eternal realities, but as it is in its own right. Since the realm of becoming is also the realm of the contingent, it is in this sense that Aristotle can be said to believe that there can be knowledge of the contingent.

It seems that Aristotle agrees with Plato when he states “ . . . it is opinion that is concerned with that which may be true or false, and can be otherwise” (89a1). But Aristotle devotes several treatises to explaining the workings of the realm of becoming, both in the most general terms (Physics and On Generation and Corruption) and in more specific matters (e.g., his biological treatises).

To explain more clearly how knowledge of the contingent is possible in Aristotle’s system of thought, I must discuss Aristotle’s metaphysics and his philosophical methodology.

Aristotle’s metaphysics

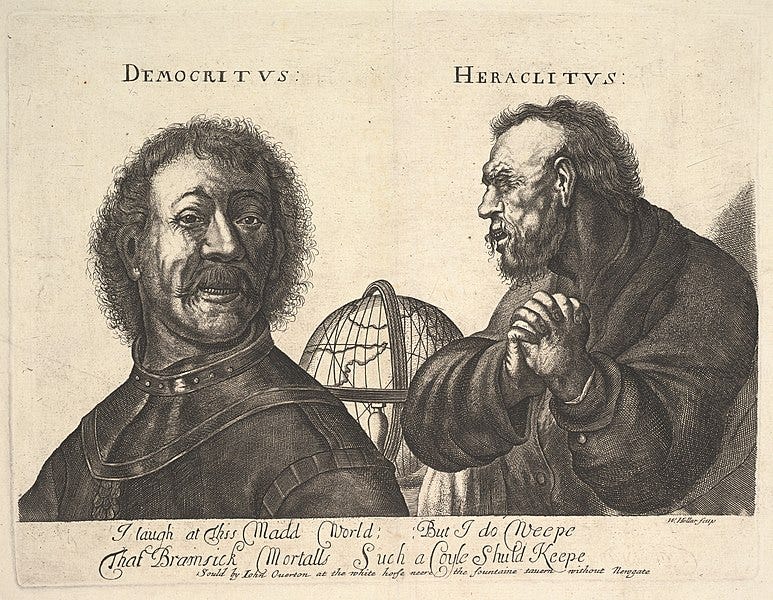

Aristotle made the world of becoming an object of knowledge by addressing the problem of change. The problem of change was a fundamental one for ancient Greek philosophers. Newton P. Stallnecht and Robert S. Brumbaugh suggest that the impasse between philosophers such as Parmenides, who thought that change was an illusion, and Heraclitus, who thought it was permanence that was the illusion, seemed so intractable that the Sophistic movement arose partially in reaction to it (The Spirit of Western Philosophy, 12).

Plato more or less accepted the view of Parmenides, but Aristotle devised an original solution to this problem. The key concepts in Aristotle’s explanation of change are substance, form, and matter. A substance is a particular entity. Aristotle viewed particular entities as real in their own right and not just instances of universals. A substance is a union of form (the defining qualities that make a thing the kind of thing it is) and matter (whatever it is in which those qualities inhere). By explaining how matter could take on different forms, and how forms could be exemplified by different matter, Aristotle is able to systematically explain change. Thus, for Aristotle, both permanence and change were real, and the perceptible world around him was neither a debased imitation of some “higher” realm nor an incomprehensible transitory chaos.

Aristotle’s methodology

The body of work that is attributed to Aristotle begins with the Organon, a collection of treatises that set out Aristotle’s philosophical method (although they do not exhaust what Aristotle has to say about method–he addresses methodological issues to some degree in most of his major works). The Organon deals with logic, dialectic, rhetoric, metaphysics, epistemology, and semantics (not in that order). The common thread that runs through all these works is that they all address some aspect of the relationship between language and truth.

Aristotle, like Plato, views the understanding as the highest human faculty, but Aristotle does not arrange the other mental activities into the sort of hierarchy that Plato does. Instead, Aristotle seems to envisage a division of labor among sensation, demonstration, dialectic, and induction, each of which has a role to play in enabling the understanding to grasp truth.

Logic provides the framework upon which the other elements of Aristotle’s methodology are related to each other. In Prior Analytics, Aristotle discusses the purely formal deductive relationships that are exhibited in the syllogism (as Jan Łukasiewicz explains in Aristotle’s Syllogistic from the Standpoint of Modern Formal Logic). It is deductive reasoning that exhibits the kind of necessary connection that both Plato and Aristotle consider to be characteristic of knowledge. Aristotle then goes on to show how syllogistic reasoning is employed in demonstration and dialectics.

Aristotle discusses demonstration in Posterior Analytics. Demonstration is deductive reasoning that proceeds, ultimately, from premises that are necessary. It might seem that Aristotle would consider only demonstration to be knowledge (since demonstrative conclusions follow necessarily from necessary premises), and indeed it is to demonstration that Aristotle applies the term “science” (επιστημη) in its strictest sense. But Aristotle’s conception of knowledge is not limited to demonstration, for, to begin with, Aristotle recognizes that the ultimate premises of a demonstration cannot themselves be proven by demonstration (for an infinite regress of syllogisms would result if all premises had to be demonstrated). These must be grasped through induction, which Aristotle sees as a function of the understanding. Aristotle says that understanding “is the only sort of state that is more exact than knowledge [επιστημη]” (100b11). But sense-perception also plays an indispensable role in induction. A number of particular instances of something must be experienced by way of the senses before the understanding can compare these experiences (using memory) and begin to make generalizations about them.

Under the heading of dialectic, which Aristotle discusses in Topics, Aristotle includes both deductive reasoning that proceeds from premises that are generally accepted but not self-evident, and inductive reasoning.

Aristotle is not completely clear about the relationship between dialectic and demonstrative knowledge. It might seem that dialectic must constitute something less than demonstrative knowledge for Aristotle, since by definition dialectic either involves deduction from premises that are not known to be necessary, or non-deductive inference. But, like Plato, Aristotle says that dialectic is the means whereby knowledge of the first principles of the sciences must be obtained (101a35).

I would say that Aristotle’s actions give us a clearer picture of his view of dialectic than his statements do. As Terence Irwin and Gail Fine note, Aristotle employs dialectic himself in his theoretical inquiries, such as Metaphysics and Physics (333). Indeed, since Metaphysics deals with “first philosophy”, it is the ultimate theoretical science for Aristotle, so if he bases this science upon dialectical methods, then I think it is safe to say that Aristotle regarded dialectic as a source of knowledge.

This does not mean that Aristotle regarded probable conclusions as knowledge. Aristotle has very little to say on the subject of probability per se. He does say that different standards of precision are appropriate for different inquiries (1094b12), and that sometimes the best that an inquiry can achieve are conclusions that are “true for the most part”, but an imprecise or qualified conclusion arrived at through deductive reasoning is not necessarily the same as a precise, unqualified conclusion arrived at through the sort of probable reasoning employed in Athenian law courts (cf. S. B. Pomeroy et. al., Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History, 345-346).

4. Evaluation

“By their fruits you shall know them.” It would beg the question to try to evaluate any of these positions based on any of the theories of knowledge these positions expound. I suggest that the value of these three approaches to knowledge can best be measured by the effects they have had on the subsequent development of Western thought.

Of the three positions described, Aristotle’s approach has proven the most fruitful. Unlike the philosophers who preceded him, including Plato, and many who succeeded him, Aristotle does not simply dismiss vast domains of human experience as mere illusion.

Aristotle’s recognition of the importance of the changing world around him, together with the methods he proposed for understanding it, are what gave birth to experimental science. This science would not have been possible had thinkers maintained Plato’s contempt for the sensible realm. As for the Sophists, while they did not scorn the mundane world of everyday human existence, they went no farther than that--they made no attempt to acquire a deeper understanding of the natural world that lay outside the walls of the polis, nor did they attempt to find any transcendent meaning or structure to existence, and they ridiculed those who did.

By dismissing so many questions as either unimportant or unanswerable, Plato’s absolutism and the Sophists’ relativism and skepticism both lead, ultimately, to intellectual complacency. It is the attitude of Aristotle, who considered everything from the lowliest mollusc on up to the Prime Mover to be worthy of investigation, that makes intellectual progress possible.

WORKS CITED

Aristotle. The Works of Aristotle. Various translators. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952.

----- Introductory Readings. Terence Irwin and Gail Fine, tr. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1996.

Bizzell, Patricia and Herzberg, Bruce. The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present. Boston: Bedford Books, 1990.

George A. Kennedy. Classical Rhetoric and its Christian and Secular Tradition, 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Łukasiewicz, Jan. Aristotle’s Syllogistic from the Standpoint of Modern Formal Logic, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Plato. Collected Dialogues. Various trans. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, eds. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961.

Sarah B. Pomeroy et. al. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.