This spring and summer I’m participating in the Michigan Vernal Pool Patrol, a citizen science project in which volunteers monitor temporary ponds that appear in the spring and dry up over the summer. These ponds are breeding grounds for certain amphibians and invertebrates that have adapted to take advantage of them. They are advantageous because they have no fish to prey on the eggs and young, since the ponds dry up, but they last long enough for the breeding cycles of the animals that use them.

The four key indicator species of vernal pools in Michigan are the wood frog, the spotted salamander, the blue-spotted salamander, and the fairy shrimp. These animals require vernal pools to breed, and individuals may return to the same spot to breed year after year. Many other animals may use vernal pools opportunistically for breeding, feeding, or shelter. For more information, visit the Michigan Vernal Pools Partnership website or their Facebook page.

During our training, a herpetologist told us that, in terms of biomass, spotted salamanders are the most prevalent species in North America. Or something like that. Spotted salamanders have been known to live up to 32 years.

Of the four indicator species, the weirdest vertebrate is probably the blue-spotted salamander, Most specimens are hybrids that have been produced by “kleptogenesis”.

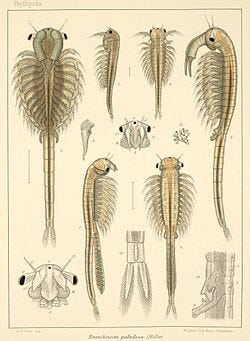

But the reproductive adaptations of the fairy shrimp are weirder, or maybe just cooler:

Another important aspect of the fairy shrimp’s life cycle is their universal ability to enter diapause, a state of biological dormancy where growth and metabolism are arrested, as an egg (or cyst). […] Once dormant, these cysts can withstand conditions as harsh and diverse as droughts, frosts, hypersalinity, complete desiccation, exposure to UV radiation and the vacuum of space. […] Once in diapause, these cysts can remain viable for centuries, and the mixing of system sediment results in the hatching of different aged cysts in each generation. This inbreeding slows the rate of selection by resisting gene flow and minimizing phenotypic variation, in turn promoting the stability of the existing, successful phenotype.

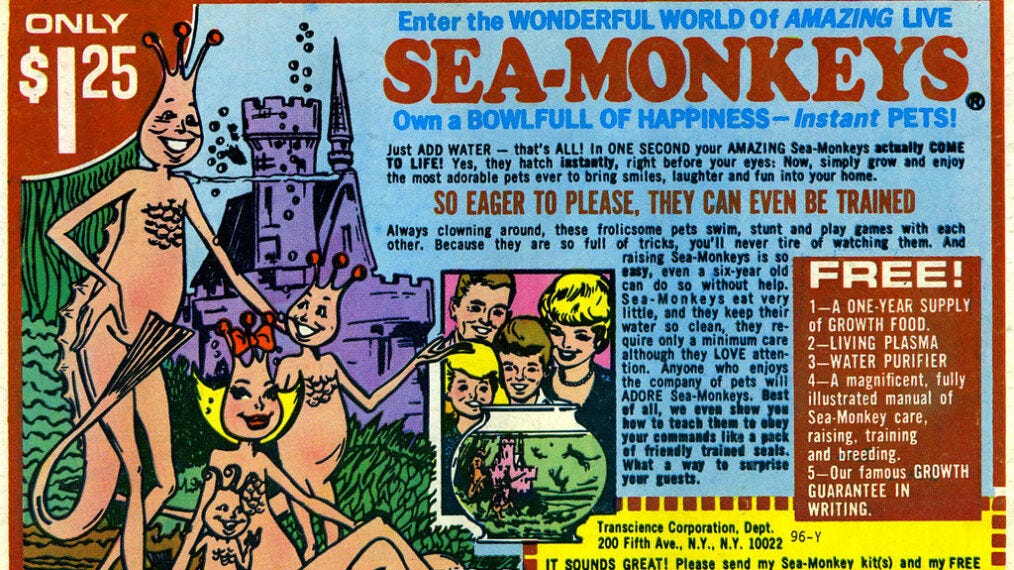

Readers of a certain age may recognize the similarity between fairy shrimp and brine shrimp, a.k.a Sea Monkeys in those comic book ads (Substacker Samantha Kemp-Jackson has a post about them).

Not particularly weird, but still pretty cool, is the wood frog.

You can hear their call in this video:

That’s the substantive part of this post. Next: a laborious inside joke.

First, some background info:

The Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham willed that his body should be preserved in the form of an “Auto Icon”. He died in 1832; in 1850 his Auto Icon was acquired and put on display by University College London.

In 1928, The House at Pooh Corner was published, continuing the series by A.A. Milne, once again illustrated by E. H. Shepard.

And now the joke:

…

…

…

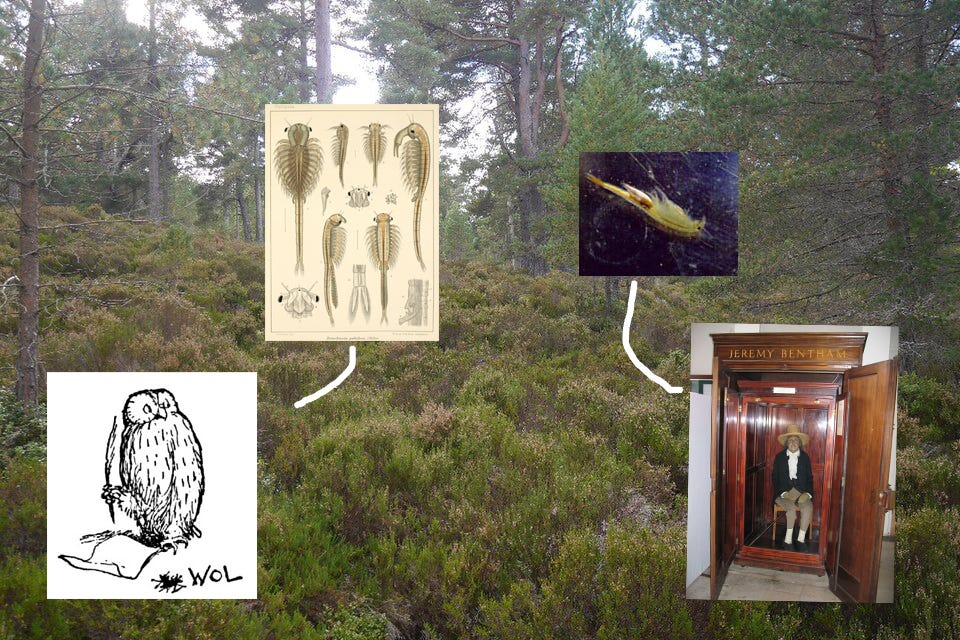

Here is A Wol discussing fairy shrimp welfare with Bentham’s Auto Icon.

In a Glen.

Disclaimer: I suck at Photoshop. This was partly an exercise to reacquaint myself with it, and partly for amusement*. It is not intended as a critique of the Shrimp Welfare Project or the earnest Utilitarians and Effective Altruists of Substack who support it. I’ll discuss my reservations against Utilitarianism in another post.

*Maybe just my own. Still counts.

Since you mentioned SALAMANDERS - apparently they're an Alpha ( ? ) fauna in the ecosystem of The Great Smoky Mtns National Park, an area I visited A LOT when I was a mere sapling of a kid. I saw a LOT of the area.

Thanks for the memories ! Cheers !

& Jeremy Bentham - an obscure reference, but I'm familiar with HIM, too.