Objections to Aristotle's Practical Philosophy

In a foreword to The Technological Society, Jacques Ellul says

The men of classical antiquity could not have found a solution to our present determinisms, and it is useless to look into the works of Plato and Aristotle for an answer to the problem of freedom. (184)

But in the same foreword he exhorts us to “seek ways of resisting and transcending technological determinants.” Aristotle shows us how to do this. For we (i.e., we citizens of technologically advanced liberal capitalist states) cannot resist or transcend the “technological determinants” that Ellul speaks of unless we have some alternative to aim at. This is a question of values, and, pace Ellul, Aristotle offers both an alternative to aim at and a system of values that justifies it.

Awareness of the social impact of technological change and awareness of Aristotle’s value theory can inform each other in significant ways. Aristotle’s practical philosophy (i.e., his philosophy of praxis) provides conceptual tools for responding proactively to technological change, and recent technological changes have made possible the realization of Aristotle’s ethical and political recommendations to a greater degree than was feasible during his lifetime.

Those familiar with Aristotle’s practical philosophy may object that my summary of it (Part 1, Part 2) has glossed over certain problematic features of his work. Aristotle’s writings on the household include those aspects of his thought that are most objectionable to contemporary readers, for it is in these writings that he endorses slavery and the subordination of women. But what he says on these topics does not vitiate his practical philosophy or its applicability to our situation, for neither slavery nor the subordination of women are essential parts of his system.

Aristotle on slavery

Aristotle’s viewed slavery as necessary for the state, but he distinguishes between necessary conditions for and essential aspects of any complex whole. Slaves, like the land that the polis occupied, were necessary for the existence of the polis, but were not part of the political community. Aristotle considered slavery necessary because contemplation requires leisure, and in Aristotle’s Greece, some could have leisure only if others had none. But modern technology has eliminated the necessity for slavery. In an often-quoted passage, Aristotle says, “if . . . the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves” (1253b 35).

More troubling is his contention that it is just for certain persons to be enslaved because they are slaves by nature. Aristotle considers and rejects two opposing views of slavery that were held many of his time. He disagrees with those who say that slavery is natural and just because, basically, might makes right and to the victor goes the spoils, but he also disagrees with those who say that slavery is not natural and is merely a convention, and an unjust convention at that. He steers a middle course between these views:

But is there anyone thus intended nature to be a slave, and for whom such a condition is expedient and right, or rather is not all slavery a violation of nature? There is no difficulty in answering this question, on grounds of reason and of fact. For that some should rule and others should be ruled is a thing not only necessary, but expedient; from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule. (1254a 20)

But Aristotle’s endorsement of slavery is not unqualified. W. D. Ross offers this useful expository summary:

It is, though regrettable, not surprising that Aristotle should regard as belonging to the nature of things an arrangement which was so familiar a part of everyday Greek life as slavery was. It is to be noted that Greek slavery was for the most part free from the abuses which disgraced Roman slavery and have often disgraced the slave system in modern times. There are certain qualifications which must be observed: (1) The distinction between the natural freeman and the natural slave is, he admits, not always so clear as might be wished. (2) Slavery by mere right of conquest is not to be approved. Superior power does not always mean superior excellence. What if the cause of war be unjust? Greek should in any case not enslave Greek. This element in Aristotle’s view may well have struck contemporaries as the most important part of it. Where to us he seems reactionary, he may have seemed revolutionary to them. (3) the interests of master and slave are the same. The master therefore should not abuse his authority. He should be the friend of his slave. He should not merely command, but reason with him. (4) All slaves should be given the hope of emancipation. (Ross, Aristotle, 250)

Even so, not only is slavery not essential to Aristotle’s view of human relationships, but Ross notes that

Aristotle’s treatment of the question contains implicitly the refutation of his theory. He admits that the slave is not a mere body but has that subordinate kind of reason which enables him not merely to obey a command but to follow an argument. Again, he says that though the slave as slave cannot be the friend of his master, as man he can. But his nature cannot be thus divided. His being a man is incompatible with his being a mere instrument. (251)

Steven B. Smith offers an interesting interpretation of Aristotle’s position in “What Did Aristotle Think About Slavery?” This essay is subtitled “Why we need to read great books closely”, and Smith’s close reading shows that Aristotle’s position is more nuanced than it might appear at first. Smith raises the possibility that Aristotle is subtly undermining the foundations of slavery — subtly, because a frontal assault on slavery would have been revolutionary, and therefore hazardous for a resident alien in Athens such as Aristotle. Smith’s essay is short and worth reading.

Aristotle on the role of women

On the subjugation of women, Aristotle claims that it is natural for men to rule. But this rule is different from that of a master, and failing to distinguish between the two is barbarous. The master rules for his own benefit (which if done correctly benefits the slave accidentally), but the rule of a husband and father is for the benefit of the wife and children (1278b).

Aristotle based his claim of male superiority partly on his interpretation of biology, which we now know to be defective. But, even if we look to modern biology, we find that there are differences between the sexes, and in light of these differences, Aristotle’s most important claim about the sexes still stands. For Aristotle’s most important claim is not about the subordination of women per se, but rather about the complementarity of the sexes. Quotes can easily be pulled from Aristotle that offend feminist sensibilities, but here is one that more clearly presents his view of the relationship between the sexes 24 :

. . . . but human beings live together not only for the sake of reproduction but also for the various purposes of life; for from the start the functions are divided, and those of man and woman are different; so they help each other by throwing their peculiar gifts into the common stock. (Nic. Eth. 1162a 20-24)

Unfortunately, the concept of complementarity has been distorted by a certain strand of reactionary discourse, which advocates rigid sex roles and female submission. For a contrasting understanding of complementarity, I refer readers to this article by Abigail Favale, Hildegard of Bingen's Vital Contribution to the Concept of Woman.

Mechanics and laborers

Another problem is Aristotle’s contention that certain occupations that are necessary for a state are degrading and render those engaged in such occupations unfit for citizenship:

. . . for no man can practice virtue who is living the life of a mechanic or laborer (1277b 33).

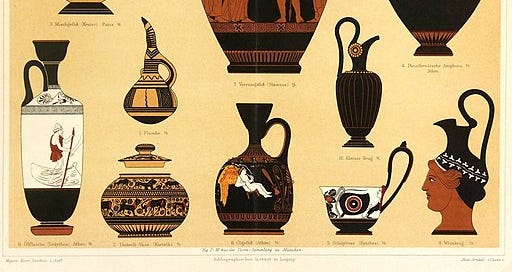

This is hard to understand when one views examples of Greek art such as those that inspired Keats; Greek craftsmen clearly achieved excellence in their crafts. It may be that much of the work was repetitive and physically debilitating; and if the workday was from dawn to dusk, then it would seem to leave little time or energy for reflection or inquiry.

At this point I would like to repeat that these difficulties arise not from the core concepts of Aristotle’s practical philosophy--eudaimonia constituted by aretē, philia, and the life of theōria--but from the prevailing social and material conditions of Greek society of Aristotle’s day. Just as the fact that the Greek language had no word for republic did not prevent Aristotle from thinking about this form of government, the fact that only a minority of Aristotle’s contemporaries could engage in theōria did not prevent Aristotle from seeing that the life of the mind was an ideal for human beings in general, and not just for a privileged few.

Technological developments have drastically altered the material conditions of life since Aristotle’s day, and social conditions have changed as well. But these changes have not rendered Aristotle’s ideal of eudaimonia obsolete. On the contrary, as a prescriptive universal ideal, this ideal fits our society more easily than Aristotle’s. For in Aristotle’s society, as in any pre-industrial agrarian society, the great majority of people had to devote most of their lives to production, leaving little time for theōria, but in our post-industrial society we have the resources to make a life of theōria available to all for at least part of their lives (although it may be that aretē and philia have become more difficult to achieve; this is difficult to ascertain).

Is the contemplative ideal realistic?

There is a different sort of objection which might now be raised against the centrality of theōria within eudaimonia. Aristotle’s claim that the life of theōria is the happiest is one that many find not troubling but implausible (cf. Barnes, in Radice). By theōria, Aristotle seems to have mainly intended the study of mathematics, “physics” (meaning the study of nature), and “first philosophy” (metaphysics)(cf. McKeon 1947). This might seem to be too narrow a basis for the good life. But there are places where he seems to view it more broadly, or as a matter of degree. I propose that it may reasonably be construed to include fine arts, religious expression, and applied research.

In Poetics, Aristotle states that people take delight in artistic representation because

. . . to be learning something is the greatest of pleasures not only to the philosophers but also to the rest of mankind, however small their capacity for it; the reason of the delight in seeing the picture is that one is at the same time learning--gathering the meaning of things . . . (1448b 14 ff.)

and

. . . poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars. (1451b 6)

These two statements suggest (a) that theōria is not only for philosophers, (b) that activities partake of theōria to a greater or lesser degree, so that while physical, metaphysical, and mathematical inquiries are the most contemplative, other pursuits can also be contemplative to some extent, (c) that aesthetic enjoyment partakes of theōria (this is further supported by Aristotle’s endorsement of music and drawing as parts of liberal education in Politics 8:3), and (d) that any activity that involves learning also partakes of theōria, especially insofar as it leads to a knowledge of universals.

Aristotle clearly intended theōria to include questions of religious significance; indeed, he takes theology to be synonymous with first philosophy (metaphysics). Contemplation of the First Mover is the highest pursuit a human being can engage in, and he believes that the First Mover’s only activity is eternal contemplation of its own perfection. This is theōria in the highest possible degree.

Admittedly, this purely intellectual appreciation of the divine differs significantly from the religious experience of most believers. Still, Aristotle does not scorn ordinary religious observance, although he might be construed as associating it with civic virtue rather than theōria. He includes “care of religion” among the purposes of life for which a state is formed (Pol. 1328b 10) and suggests that old men be entrusted with priestly duties after they have completed their military and ministerial duties to the state (1329a 30).

The key to theōria is wonder. “For it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and first began to philosophize” and “even the lover of myth is in a sense a lover of Wisdom [philosopher], for the myth is composed of wonders” (Metaphysics, 982b 11 ff.).

Some interpreters of Aristotle might object that applied research, in particular, be excluded because Aristotle takes theōria to be valuable solely for its own sake. But here again, developments subsequent to Aristotle’s lifetime cast his thought in a clearer light: whereas once technological innovation was independent of theoretical inquiry, now “pure” or basic research has led the way for important applications.

Aristotle’s exaltation of theōria is based not only upon the fact that we do it for its own sake (which may be true even if other benefits result from it if the other benefits are merely secondary or incidental motivations), but on the fact that it engages our highest faculties. This might allow us to construe theōria even more broadly. There may be a kind of “everyday theōria” accessible to all occupations. Those who have learned how to reflect on their experiences in the appropriate way (that is, in the spirit of wonder) may find themselves making discoveries in the course of the most mundane activities, even those that Aristotle himself would not have associated with any kind of intellectual virtue.