In 2016 I seriously considered voting for Elizabeth Warren in the presidential primary. The financial sector is out of control in the US, and Warren seemed to me to be the one candidate who had both the necessary knowledge and willingness to take on the big banks and insurers. I read her book about “the two-income trap”, and it confirmed my positive impression of her. Unfortunately, she did not do well in the early states, and she dropped out of the race before Michigan’s primary took place. I recently re-read her book.

In 2023 in the US, among married couples with children, it is normal for both partners to be employed full-time. In 1970, a single breadwinner was the norm, at least among middle-class households. Yet, as women entered the workforce in increasing numbers after 1970, bankruptcies rose. Why are so many two-income families going broke?

Elizabeth Warren and her daughter Amelia Warren Tyagi take up this question in The Two-income Trap: Why Middle-Class Parents Are (Still) Going Broke. Originally published in 2003 (when Prof. Elizabeth Warren was an academic expert on bankruptcy law, and before she entered politics) and updated in 2016, Warren explains why the shift from single incomes to dual incomes has made families less financially secure. (I will refer to the authors jointly as “Warren” here.)

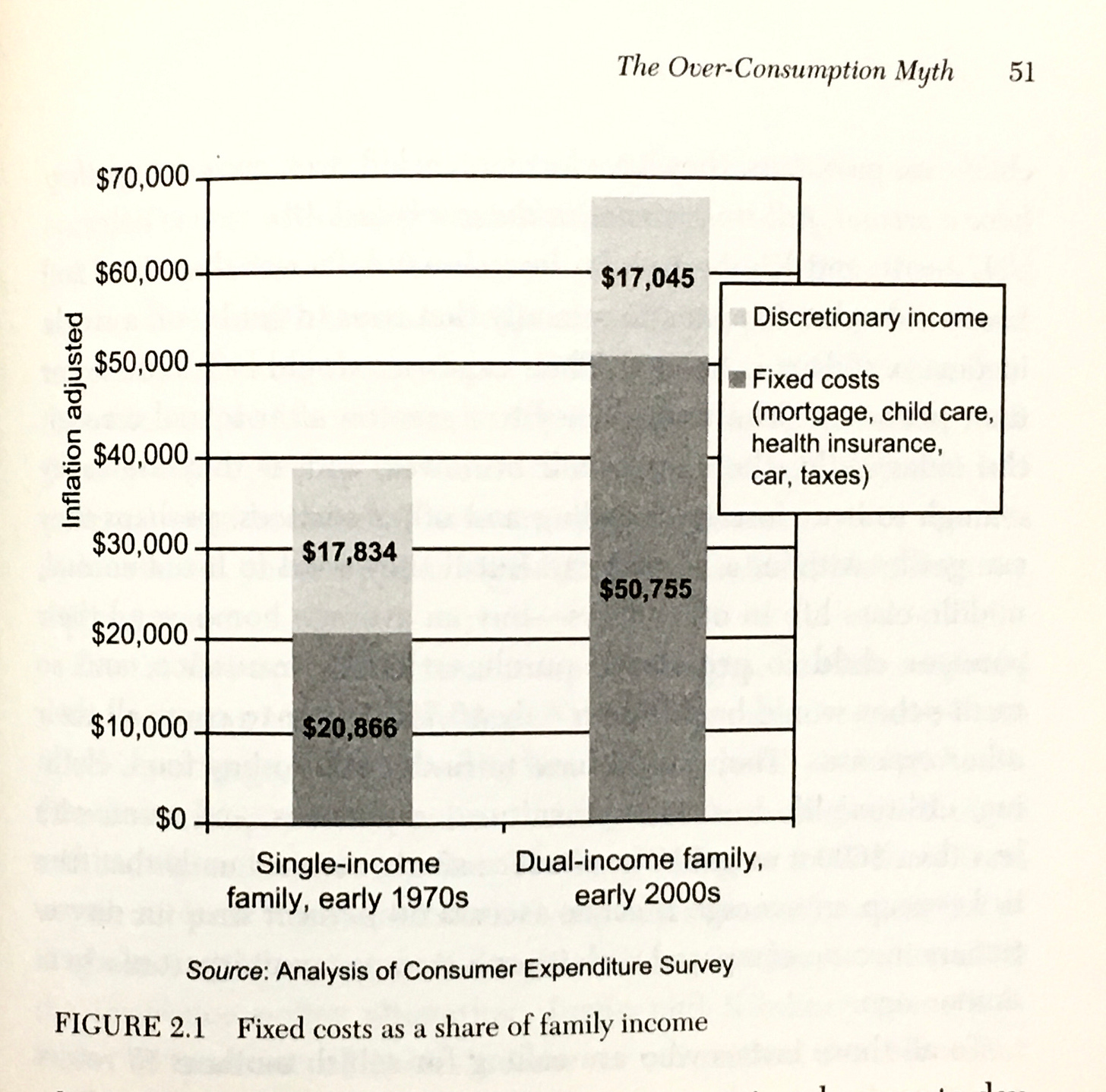

Where did that extra income go? Warren explains that it did not go to excessive consumption. Households are not going bankrupt because they are overindulging on luxuries [1]. The extra income was largely spent in a bidding war to buy houses in safe places with good schools. Rising healthcare and education costs, especially daycare and higher education, placed additional strains on household income, but middle-class incomes remained flat despite economic growth. On top of that, deregulation of banking and credit cards allowed predatory lending to take advantage of those strained households, and changes to bankruptcy law exacerbated the impact of that predation.

When a couple commits to a mortgage that one salary alone cannot support, they are, to borrow a phrase from Francis Bacon, “hostages to fortune” [2]. In order to earn two incomes, many couples must obtain a second car and childcare, leaving little for savings. Yet job loss for one reason or another is very common, and when that happens, if the couple cannot meet their obligations on one salary, they are in danger of losing everything.

Warren shows how mothers used to be an “all-purpose safety net”. In a typical one-income family of 1970, if Dad lost his job, Mom could get a job to help make ends meet until Dad went back to work. If an elderly family member became infirm or a child became seriously ill, Mom was available to provide care. The two-income family of the 21st century does not have this backstop, for Mom has already been committed to the labor force. If a family member needs extensive care, the couple must either pay someone else to provide it or one partner must quit their job to become a caregiver. When the couple is barely making ends meet on two salaries, and they have commitments such as mortgages and car payments that they cannot just walk away from, the ordinary vicissitudes of life can lead to impossible dilemmas. Divorce can be both a cause and effect of these strains. Financial stress is a major contributing cause of divorce, and divorce also contributes to bankruptcy for one or both of the former partners.

So the problem is that, despite steady economic growth, middle-class incomes have not kept up with the rising cost of a middle-class lifestyle, and families have tried to bridge that gap by putting mothers to work for employers. In response, Warren offers both broad policy responses and advice for couples.

Her policy responses are, first, to undo the deregulation of banking and tighter restrictions on consumer bankruptcy for which the financial industry successfully lobbied, and second, to decouple access to high-quality education from place of residence, publicly subsidize childcare, and freeze college tuition

On the first point, Warren names and shames Joe Biden and Hilary Clinton for siding with the financial industry on these regulations. Events since the original publication of this book have sufficiently – and repeatedly – vindicated Warren’s take on these things, so I will not dwell on them.

On the second point, Warren advocates publicly funded preschool, a voucher system for K-12, and tuition freezes for higher education. Few would oppose the general idea that adequate education should be available to all children regardless of where they reside, but Warren’s specific solutions are inadequate to solve this problem. At best they are palliative. A voucher system might weaken the connection between home price and school district, but would not eliminate it. There would still be competition for spots in the best schools, and, assuming these are not boarding schools, then families would still have to live close enough to get their kids there every morning, not to mention the additional transportation costs involved. Publicly funded preschool might allow families to keep more of the money that a second income generates, but would not remove the pressures that necessitate both parents working in the first place. Tuition freezes might add some discipline to university spending but will not address the disinvestment in public higher education that has taken place since the 80s, nor will it counteract the changes in society and the economy that have made post-secondary education practically indispensable for most of the middle class.

Warren recognizes that there must be collective action to solve these problems, but she also recognizes that change will take time, and she has advice for families who are struggling to survive in the meantime. She offers a “financial fire drill” to help families determine whether they are stretched too thin, and also has practical advice for families that are already in financial trouble.

She also considers the option of not having children. (I recall seeing articles about “dinks” — dual income, no kids — in the 80s, not long after the articles about “yuppies”). Elizabeth Warren is a feminist and a mother; she does not want women to be forced to choose between careers and motherhood, nor does she want to to bring back rigid gender roles. She also worries about the implications for the nation’s future: “What happens to a nation that that rewards the childless and penalizes parents?”, she asks (p.175).

On her final page, Warren warns

The collective pressures on the family—the rising costs of educating their children, the growing insurance and medical bills, the rising risks of layoffs and plant closures, and the unscrupulous tactics of an unrestrained credit industry—are pushing families to the breaking point. America’s middle class is strong, but its strength is not unlimited.

[…][the middle class] is under assault […]. Their willingness to send 20 million mothers into the workplace had unintended fallout, but it was rooted in a powerful desire to create a better future for their children. Their failure to demand accountability from their politicians and the organizations that purport to speak for them has left them weakened. But we believe that collectively and individually these families have the tools to change the structure of their schools, to bring their politicians to heel, and to fight back against big businesses that would steal their economic vitality. They can release the trap. (p.180)

After reading this book again in 2023, I find that it holds up well. This book offers three services to the reader: first, it offers an explanation of how so many middle-class families got into financial trouble; second, it offers policy prescriptions to address the problem; third, it offers concrete practical advice to couples.

The book succeeds on the first and third points. On the second, it does not go far enough. She is correct to focus her analysis on families, rather than individuals, but she fails to consider an obvious solution: shorter working hours.

If we do not want to go back to the single-breadwinner norm of 1970, then both parents must work. But why must both parents work 40-60 hours a week, i.e. 80-160 hours total, when one parent working 40-60 hours a week sufficed in 1970? Families are giving too much to the labor market and getting too little in return. In 2023, people are finally starting to wake up to the need to claw back those hours, as can be seen from the growing number of articles about 4-day or 32-hour workweeks and the successful pilot programs of these shorter workweeks.

(Even those do not go far enough. We should be moving towards a 1200-hour work year. Two parents working 1200 hours would be 2400 hours a year — closer to what that single breadwinner supported a family on in 1970. A 1200-hour work year could be 30 hours per week for 40 weeks, 24 hours per week for 50 weeks, or many other permutations.)

That said, Warren’s book remains relevant and valuable in 2023. The book is aimed at a lay audience and avoids jargon. Warren’s clearly written explanations are supported by data and representative examples. I would go so far as to suggest that Warren’s book should be required reading in marriage preparation classes or couples’ counseling, so that prospective couples can not only avoid financial pitfalls that can wreck a marriage, but also see more clearly how their household fits into the bigger picture of social and economic justice.

Notes

[1] Warren mentions Juliet Schor among those who scold Americans for spending too much on luxuries. I do not think this is a fair characterization of Juliet Schor’s critique of consumerism; see my piece on Schor’s Plenitude. But Plenitude came out in 2010, so it is possible that Schor’s thought had evolved since 2003 edition of Warren’s book, and Schor may have taken Warren’s criticism into account. Schor in 2010, unlike Warren in 2016, explicitly calls for shorter working hours.

[2] “He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune; for they are impediments to great enterprises, either of virtue or mischief.” – Francis Bacon, Essay 8.