Michael Witgen’s An Infinity of Nations (2012) describes how some of the indigenous peoples of the North American interior responded to European and eventually American and Canadian expansion. It is focused primarily on the Anishinaabeg in the Great Lakes region during the 17th century.

Witgen’s interpretation relies on a conceptual framework that was new to me. The central concept of this framework is the Native New World. Contrasting with the idea of the New World as “[…] a place of European discovery, conquest, and national reinvention”, Witgen shows that “[…] there were Native peoples in the interior of the continent who had made the same transition and transformation, and in the process created a distinctly Native New World.” (7) The “emergent world economy” (118) of the 17th century presented the indigenous people of the North American interior with opportunities and challenges.

By the last decades of the seventeenth century new peoples and things moved between the colonized east coast of North America and the indigenous western interior. […] The vast interior of North America was occupied and controlled entirely by Native peoples, making any imperial claims over this landscape nothing more than fiction. […] The struggle to control the movement of people, things, and ideas between the Atlantic World [i.e., that of the European powers and their new colonies] and the indigenous west [led to] the creation of a Native New World in the heartland of North America.

[…]

Modern North America was shaped by the clash and ultimately the coexistence and parallel development of the Atlantic World and the Native New World. Complex and shifting alliances and exchange relationships connected autonomous Native social formations in the west to Europeans and European-allied Indians in the east. […] (116-118)

The Anishinaabeg were (and still are) the Algonquian-speaking Native peoples of the northeastern woodlands who had similar customs and mutually intelligible dialects, including, among others, the “People of the Three Fires”: the Ojibwe (Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa), and Bodéwadmi (Potawatomi). The other major groups of Native peoples in the Native New World whose territory bordered that of the Anishinaabeg were the Dakota (the Lakota or Sioux) of the western plains, and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) of the east. The Anishinaabeg who settled in the Great Lakes region were driven there by pressures from European settlements on the Atlantic coast, the diseases they brought, and by Haudenosaunee raiders. There were also some smaller groups in the region, including the Wyandot (Huron).

The Anishinaabeg were largely allied with the French. The French, like the Spanish and English, claimed vast portions of North America that they had little or no effective control over. The French tried to extend their influence through a system of alliances and trade relationships with Native peoples, but the French proved unable to provide sufficient protection or trade goods to satisfy their partners.

The fur trade was the major source of revenue for New France, and the colonial authorities relied on Native trappers to supply it. But authorities in Montreal and Paris had to contend with encroachments from unauthorized French traders (the coureurs du bois) and the English Hudson’s Bay Company. Native groups also competed with each other to obtain favorable terms of trade and to control the best beaver hunting grounds, and to gain French or English support against their rivals.

Witgen provides detailed accounts of specific incidents and individuals in a way that makes sense of these complex relationships without obscuring the big picture that he wants to convey. Having lived most of my life in the Great Lakes region, it was interesting to learn the stories behind familiar names and places like Huron, Wyandotte, Cass, Schoolcraft, Duluth, Cadillac, Okemos, and many others. I would recommend this book to anyone who wants a fuller picture of the history of this region, especially my fellow Michiganders.

Happy Thanksgiving 2023 and happy Native American Heritage Month!

Added 2024: When I posted this in 2023, I was not entirely satisfied with what I wrote. I feel like I did not adequately express what I found most interesting about this book, which was how effectively Witgen integrates Native concepts into his account. I say “effectively” because these concepts help make sense of the events described.

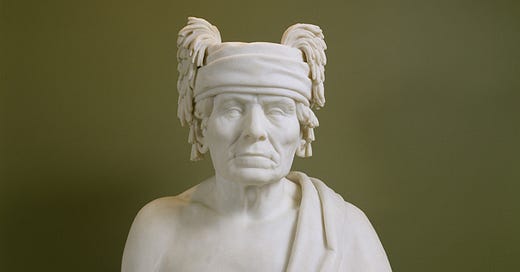

An example of this that has stayed with me over the past year is the concept of “shape-shifting”. This concept appears on page 1, and it reappears at several places. Witgen begins his work with a prologue, subtitled “The Long Invisibility of the Native New World”, in which he introduces the Native New World as the key concept of his interpretive schema, and also illustrates the concept of shape-shifting as a element of the Anishinaabe worldview. He begins his prologue with an anecdote about encounter in 1832 between the Ojibwe leader Eshkibagikoonzhe (a.k.a “Gueule Plate” or “Flat Mouth” – see photo, above) and Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, a federal Indian agent for the Michigan territory. The encounter is imagined from the Ojibwe leader’s point of view. Here are the first two paragraphs of Witgen’s work:

Eshkibagikoonzhe felt anger, betrayal, and a deep sense of disappointment. He sat behind a table in his home at Gaazagaskwaajimekaag (Leech Lake), an immense lake with nearly two hundred miles of shoreline. Five medals, several war clubs, tomahawks, spears, all splashed with red paint, lay on the table before him. Eshkibagikoonzhe painted his face black for this council session. The Bwaanag (Dakota) had recently killed his son and he mourned his loss. All of the people, the Anishinaabeg (Ojibweg), felt the pain of this death, the loss of a future leader. Eshkibagikoonzhe summoned the man he held responsible for his son’s death to join him at council in his home. Now he waited.

The man he waited for came from a new power that had risen in the east. It had been a little over three decades since Eshkibagikoonzhe (Bird with the Leaf-Green Bill) began to hear about this new people. They were called Gichimookomaanag (The Long Knives / Americans), and they had a reputation as ruthless killers with a hunger for Native land. The Long Knives had been part of the Zhaaganaashag (British), but they shape-shifted, and now the Gichimookomaanag and the Zhaaganaashag formed two rival peoples.

Of course, every culture has concepts related to change, but this Anishinaabe idea of shape-shifting seems to be associated with a flexibility that may have helped them survive the rapid and multi-dimensional transformations that they faced during the period this book covers. Present-day Americans might need such adaptability in the near future.

To be continued . . .