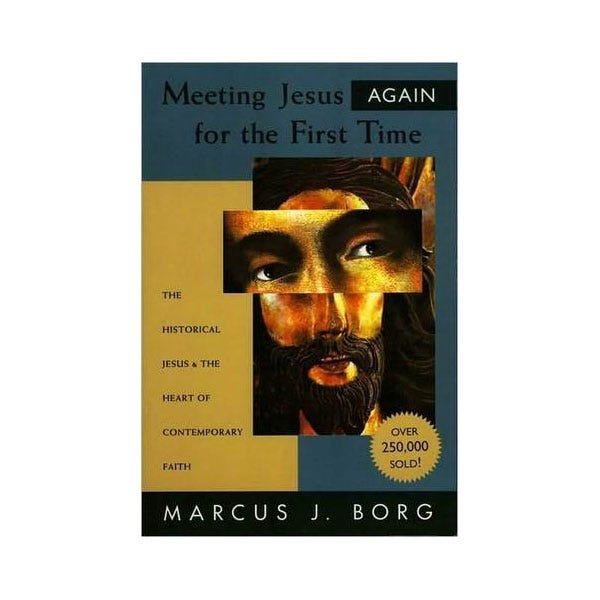

Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time: The Historical Jesus & The Heart of Contemporary Faith

By Marcus Borg (1942-2015), Hundere Distinguished Professor of Religion and Culture at Oregon State University.

Summary:

Borg examines what the available historical and scriptural evidence tells us about the historical person of Jesus and what he taught during his lifetime (the "pre-Easter" Jesus) and what relevance this has for understanding the Christ of faith (the "post-Easter" Jesus).

Borg uses the methodology and findings of the Jesus Seminar to interpret the canonical Gospels and related apocrypha, along with other textual and experiential evidence.

Borg argues that teachings of the pre-Easter Jesus were probably "theocentric, not christocentric -- centered in God, not ... in a messianic proclamation about himself", and "noneschatological ", i.e., Jesus did not expect "the supernatural coming of the Kingdom of God as a world-ending event in his own generation."

Borg offers a "sketch" of the pre-Easter Jesus that is organized around four "broad strokes". Jesus was:

"a spirit person ... with an experiential awareness of the reality of God."

"a teacher of wisdom", specifically, "a subversive and alternative wisdom."

"a social prophet" who "criticized the elites (economic, political, and religious) of his time."

"a movement founder" calling for a new approach within Judaism; this movement "eventually became the early Christian church."

The picture that emerges from these strokes emphasizes immanence over transcendence, experience over belief, and compassion over holiness/purity. Borg also frequently draws on feminist scholarship to challenge overly masculinized conceptions of God.

Borg spends two chapters on wisdom in order to examine the human and divine dimensions of the wisdom of Jesus. At the level of human conduct, Jesus "directly attacked the central values of his social world's conventional wisdom: family, wealth, honor, purity, and religiosity", and his message also implicitly attacks contemporary secular values of "achievement, affluence, and appearance". Against these lives of external "requirements and reward" Jesus calls for "internal transformation" and "a deepening relationship with the Spirit of God". Borg also examines Wisdom as divine, and reviews the development of this idea from the Wisdom Woman of the Old Testament to the second person of the Trinity incarnate in Jesus that emerges in the synoptic gospels, Paul, and John.

Borg suggests that we look at Scripture using three "macro-stories" as an interpretive framework, viz.

the Exodus story of "bondage and liberation"

the story of Exile and Return, which in which we are lost in alienation and separation until we come home to God's presence.

the Priestly story of "sin, guilt, sacrifice, and forgiveness". (Not to be confused with the P source posited by biblical scholars.)

All three stories are important and yield powerful metaphors for Christian life, but Borg argues that the Priestly story has become too prominent in Christianity at the expense of the others, leading to an unbalanced image of Jesus and his message.

Comments:

I’m not qualified to evaluate the details of Borg’s historical or textual analysis, so what follows is more of a personal response than a critique.

Borg’s interpretation is mostly what one would expect from a liberal mainline Protestant Bible scholar of that generation, and some of it is at odds with my Catholic understanding of theology, but Borg's "theocentric" interpretation of Jesus resonated with me. I think this view of Jesus can be reconciled with the dogma of the dual nature of Jesus by understanding Jesus as the incarnate second Person of the Trinity, which in turn can be understood as the Wisdom of God/Logos. The emphasis on compassion over purity also rang true for me.

I read this for a book group at my parish. I, an older Gen Xer, was the youngest person in the group when I attended. My parish serves a university town, and this group, which includes some retired faculty, is more liberal than the average Catholic church-goer.

Although I voted the same way as most of these folks probably did during the last presidential election, and we probably share similar views on certain questions of discipline and morality such as women priests, priestly celibacy, and contraception, I found myself disturbed by some of their views on theology, including dogma and Scripture. Some were unorthodox, some were uninformed.

Some seemed ready to view Jesus as simply a holy man. I did not expect to have to rehash the Arian controversy and defend basic Catholic doctrine in a Catholic reading group. At one point, I asked, “If that’s what you believe, why not just be a Unitarian?”, and my question was neither rhetorical nor hostile.

But no sooner had I asked it than an obvious answer occurred to me. This book discussion group has been running for over a decade, maybe closer to two, and several of the members have been participating since its beginning. These meetings are an important source of social connection and spiritual sustenance for them.

Certain reactionary Catholics who are active on social media might deride this group as stereotypical “Boomer Catholics”, but unlike many of that generation, and many more of younger generations, these Boomers have remained engaged in their faith community and connected, albeit tenuously in some cases, to the Church as a whole.

Which raises the question, what makes us church (a church, or the church that we are, or the Church)? Is it creed, community, or continuity? Some combination of all three, clearly. I was going to attempt to say with more precision how these factors interrelate, but I find that the answer eludes me, so I’ll leave it there for now.