What is the relationship between knowing that and knowing how? And why does it matter?

Knowing that (KT hereafter) has received considerable attention from philosophers. Explicating KT is what epistemology is usually taken to be all about. Knowing how (KH hereafter) has received less attention from philosophers. I shall argue that the two are interdependent. Along the way I hope to suggest a response to skepticism and also shed some light on certain problems pertaining to the philosophy of science.

Knowledge and belief

In the analytic tradition, KT has come to mean justified true belief, plus whatever condition satisfies the Gettier paradox. Truth is generally interpreted as some sort of correspondence between beliefs and the reality they describe or represent. Belief is analyzed in terms of dispositions to act or behave in certain ways. True beliefs are justified just in case they are either inferred from other true beliefs or self-evidently true. This account of KT has its shortcomings, but I shall take it as my starting point.

Given that beliefs are dispositions, what does it mean to say that a belief is true? Propositions, not dispositions, are truth-bearers. An answer might be that beliefs, unlike other dispositions, have propositional content, and so to say that a belief is true is shorthand for saying that the content of that belief is true.

But what does it mean to say that a disposition has content? It could mean that those who have that belief/disposition assent to the propositional content associated with it, that is, they represent it to themselves to be true. But if this is the only link between truth-bearers and our beliefs, then the connection between our beliefs and our actions (other than the action of assenting to a proposition) becomes obscure. Furthermore, given an internalist view of knowledge, this view seems to make most of our putative knowledge susceptible to all the usual skeptical arguments. We cannot step outside ourselves and check the correspondence between our representations and the world, and in most cases we cannot show that the propositions we assent to are either self-evident or deduced from propositions that are self-evident, and so the possibility of error arises. Against an externalist view of knowledge, the skeptic can shift the attack from individual propositions to our knowledge as a whole.

With this in mind I suggest that the content of belief needs to be distinguished from the import of belief.

A belief is a disposition to act in certain ways, including assenting to the proposition that constitutes the content of that belief. Assenting to a proposition is the mental activity of representing that proposition to oneself as true. This representational aspect is what distinguishes beliefs from other dispositions, and the particular propositions assented to are what distinguish one belief from another. So to believe a proposition one must assent to it; the proposition assented to is the content of the belief (the belief-content), e.g., the content of belief X might be the proposition that copper wires conduct electricity.

The import of several beliefs is, roughly, the way those beliefs inform the actions of the believer. The import of a set of beliefs is derivable from the contents of those beliefs taken conjointly. The import of a set of beliefs is a set of one or more propositions (belief-imports) of a specific kind: they are conditionals that assert that if a certain acts are performed, then certain consequences will follow, e.g., the import of beliefs X, Y, and Z may include the proposition that if a certain switch is thrown, a light will come on. Thus, it is belief-imports, and not belief-contents, that inform our actions.

("The import of beliefs" is a collective noun referring to a set of propositions, while "belief-import" is a countable noun referring to a particular proposition that may be a member of that set.)

Truth and action

This distinction between belief-contents and belief-imports allows an explication of the connection between belief and action. Every voluntary act requires three elements: a) the intent to bring about certain experienced consequences, b) the ability to perform a certain procedure, and c) the belief-import that the performance of that procedure will result in the intended consequences.

A belief-import is true to the extent that the consequences experienced by the subject of the belief as a result of an action informed by that belief-import match the consequences predicted by that belief-import. So this is a correspondence theory of truth, but the correspondence that matters is not a correspondence between a belief-content and external reality; rather it is a correspondence between a belief-import, on the one hand, and the relationship between an act and its experienced consequences on the other.

Justification may be viewed in either foundational or coherentist terms for the purposes of this discussion. In foundational terms, a belief-import is justified just in case it is ultimately derived from (or is at least consistent with) the contents of foundational beliefs. In coherentist terms, a belief-import is justified insofar as the set of belief-contents it is derived from is coherent.

All the beliefs that a knower holds (a knower's "belief system" hereafter) collectively represent (via belief-imports) the procedures that they can perform together with the consequences of doing so. Thus a belief system represents the level of control that a knower can exercise over their experiences.

Knowing how, knowing that, and options

So where does KH come in? Above, I said that every intentional act requires the ability to perform a certain procedure. "Ability" here requires KH.

All voluntary action is mediated by KH. KH is an agent's ability to intentionally reproduce interpreted experience of a particular kind in particular circumstances. This ability consists of the procedures that are represented by the belief system (by procedure I mean a set of behaviors and/or mental operations involving particular means to achieve particular ends). These procedures are the point of contact between the representations of consciousness and the "exterior" world, that is, all that is not the knower. For the procedures belong to both.

The procedures are the options that are open to the knower qua willing self. But being represented to a knower as one of that knower's options is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for that option to exist; the other necessary conditions are the particular circumstances mentioned in the preceding paragraph--aspects of the knower's environment, the exterior world.

So both KH and KT are necessary for voluntary action. KT is the representation of available options, and KH is what KT represents. Beliefs are KT just in case they represent options that are really open to the knower, and the procedures of KH are only options if they are represented as such. Thus KH and KT are interdependent.

This account raises questions about the faculties of representation and interpretation. KH reproduces interpreted experience, that is, experience that has been divided, classified, and evaluated. To what extent is this process under voluntary control? If interpretion is voluntary it would seem to be itself a kind of KH.

Similarly for representation--while KT consists of representations, the faculty of representation itself may be a kind of KH. For now I will have to settle for a disjunction: representation and interpretation are either forms of KH or primitive functions of consciousness.

Skeptical concerns

With all of the foregoing in mind I will now propose a characterization of knowledge that includes and supersedes the justified true belief conception with which I began this essay: knowledge is the awareness (= conscious representation) of one's options. To paraphrase Peirce: Consider what options we conceive the object of our conception to entail; then, our conception of these options is the whole of our conception of the object1.

Does this conception of knowledge stand up to skeptical objections any better than justified true belief? The application of correspondence to belief-imports rather than to belief-contents makes truth a matter of degree. For the import of a belief system is ultimately a holistic and dynamic phenomenon. A knower’s belief system as a whole represents the level of control that a knower exercises over his or her experiences. This can be represented more or less accurately, and the accuracy can change over time. To a great degree, the proof is in the pudding, as it were. When I kick a stone and get the expected experiential result, my belief-import is vindicated to that degree, even if my belief-content is not. So even if the ontology of the external world eludes us, we can come to know our limits2.

Science and technology

This account of KT and KH lends itself to a parallel understanding of the relationship between science and technology. Belief systems represent the level of control that knowers exercise over their experiences. Control over experience entails some degree of control over the exterior world or environment in which the knower is situated.

Assuming that there are multiple knowers, the possibility emerges that knowers may use each other's KH to control their own experiences. Knowers acting in concert can sum their KH, as it were, to produce a joint level of control--that is, a shared pool of KH that the members of a community of knowers can draw upon.

But it is possible that a community of knowers may gain and lose individual members. If the joint level of control is to be maintained it must not be dependent upon particular knowers. Maintenance of joint control therefore requires that the joint level of control be transmissable from knower to knower. This transmissable joint level of control constitutes technology3.

What does this have to do with science? Science is the communicable representation of this transmissable joint level of control. I speak here of science as epistemē, not science as praxis or technē; nevertheless, there is by this definition necessarily a social aspect to science. Every knower has a representation of their own level of control; it may or may not be communicable. Even if it is communicable it may only convey their own level of control without conveying their contribution to the joint level of control. Even if it conveys their contribution, it may not convey the transmissibility of that contribution. Science aims at something more general--the communicable representation of the level of control attained by a community of knowers that is not dependent on any particular member of that community.

What does this have to do with progress? Advances in technology (the transmissable joint level of control exercised by a community of knowers) are dependent upon the discoveries or inventions of individual knowers. In order for a discovery or invention to constitute a technological advance, a communicable representation must be formulated that will allow the knowers in the community to represent to themselves the new options made available to them by the discovery.

Thus scientific and technological advances are interdependent in much the same way that KT and KH are interdependent.

Progress and Paradigms

This view of KT, KH, science, and technology rules out a strictly realistic construal of the claims of science. But I consider this a point in its favor. For my view generates an account of scientific progress that is not susceptible to certain objections that have been raised against scientific realism. Specifically, this view suggests a solution to the Kuhnian problems of "incommensurability" and untranslatability of different paradigms (Kuhn, 1970, Ch. XII).

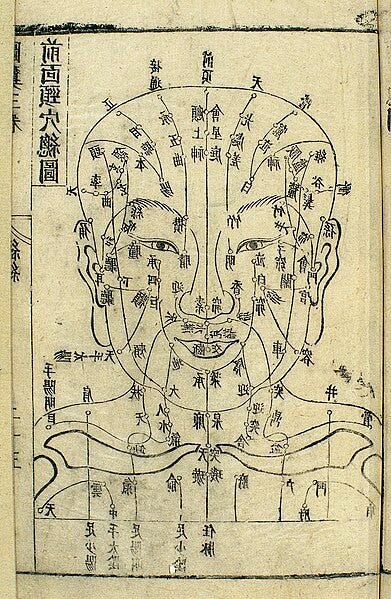

Since correspondence does not apply at the level of belief-contents, a subject has more than one way to skin a cat, so to speak, when dealing with its environment. For example, students of traditional Asian medicine and martial arts will assent to propositions that assert the existence of some force known as chi (or qi). Whether such a force is real in the way that Westerners think the forces of electricity and gravity are real is irrelevant. The import of beliefs derived from assertions about chi is that these students can bring about certain consequences if they perform certain procedures. These students can in fact reliably bring about these consequences through acts informed by the import of these beliefs. So these beliefs are true, and since the techniques involved are transmissable, beliefs about chi and the associated techniques constitute a representation of the transmissable joint level of control exercised by the community of knowers who subscribe to these beliefs. To the extent that this representation is communicable, it constitutes science, even if it is not wholly consistent with Western science (just as relativity theory and quantum theory are both science, even though they are not wholly consistent with each other).

This is the answer to the problem of the incommensurability of different paradigms. The accuracy of the communicable representations of the transmissable level of control that humans exercise over their environment is the standard by which competing paradigms may be measured. The fact that the terms of one paradigm may not be translatable into the terms of the other is irrelevant for purposes of this evaluation. The paradigm that better represents the level of control is the superior one.

However, since technology continuously advances, science must be capable of change if it is to continue to be accurate. Some belief systems do not readily change to accommodate new technological advances and therefore become less accurate and ultimately less scientific.

The transmission of KH

I have referred several times to the "transmissable level of control". Such transmission must involve the transmission of KH from knower to knower. How is this effected?

Control of the environment is mediated by KH. KT can be transmitted verbally but KH cannot. KH must be acquired by directly interacting with the environment. An instructor cannot convey mastery of a skill by verbal instructions or even by modeling — these methods merely convey to the learner the actions that must be performed in order to begin to acquire the skill.

There are exceptions to this; the ability to acquire language and the ability to transmit and decode instructions for certain simple motor activities and mental operations are innate. Upon this innate foundation, the procedures that must be performed to acquire more complex forms of KH can be conveyed.

The transmission of KH is affected by technological change. The procedures of KH are a point of contact between the knower and the world: the procedure embraces both the knower's behavior and the means employed. That is, the procedure is holistically specified in terms of tools and operations performed with those tools; neither the tools nor the operations can exist per se without the other, and the conjunction of the two should be thought of as a single instrument at the disposal of the knower. But technological change can shift the composition of such an instrument; a procedure consisting of complex operations with simple tools may be replaced by a procedure consisting of simple operations with complex tools. This is what occurs when skilled craftsmen are replaced by advanced machinery operated by semi- or unskilled workers. Such a change may or may not raise the level of control, but it will facilitate the transmission of the level of control (as well as having political and social consequences).

Conclusion

Knowers are also doers, and essentially so. That being the case, if knowledge is a species of belief then the connection between belief and action must be addressed before knowledge can be understood.

I have suggested that this relationship is one of mutual dependence, and I have attempted to describe to some extent the interrelationships between knowing that and knowing how. In support of my view, I claim that my view generates a response, if not an outright solution, to classical skeptical concerns. My view also explains the possibility of scientific progress and clarifies the relationship between science and technology.

I must acknowledge that in this essay I have emphasized description rather than argument. I have concentrated on exploring some of the consequences of viewing knowledge as the awareness of one's options, providing only a minimum of motivation for viewing it that way. Accordingly, and also due to unresolved issues pertaining to interpretation and representation, my conclusions must be tentative and programmatic. I hope I have shown why I believe that this approach may prove fruitful4.

"Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object." (C.S. Peirce, in Buchler, 1955).

Unfortunately, an account of how this conception of knowledge deals with the problem of induction must await clarification of the role of interpretation. If interpretation is KH, then it may be that induction is a sort of interpretive schema that knowers impose on their experience with varying degrees of skill. If interpretation is an involuntary primitive function of consciousness then I may find myself forced towards some sort of Quinean naturalism with regard to induction. But until I have a better handle on the semantic and phenomenological issues surrounding interpretation and representation, I cannot say that my view fares any better against the problem of induction than other views.

Less abstractly, we could think of "transmissable joint level of control" in terms of the amount of energy at the disposal of humans and the ways humans can put that energy to use.

I am using technology in the sense technique(s) or technical means, not in the sense of the study of said technique(s) or technical progress. (It’s a pity this distinction is no longer observed in contemporary usage, and that Lewis Mumford’s term technics now only exists as a brand name.)

I would like to mention in passing some of the ramifications of this view might have for metaethics, and vice versa. Elsewhere I have argued that moral skepticism is incoherent, meaning that if moral facts exist, they must be known or at least knowable. Now, I have defined knowledge in terms of options. If moral facts exist, then fulfilling one's obligations is always an option, since ought implies can. This raises the possibility of defining knowledge in terms of obligation. To again paraphrase Peirce, consider what obligations we conceive the object object of our conception to entail. Then, our conception of these obligations is the whole of our conception of the object.

Bibliography

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. "How to Make Our Ideas Clear", in Philosophical Writings of Peirce, Justus Buchler, ed. New York: Dover, 1955.

Robertson, M. D. “Science, Technology, and Progress”. Proceedings of the Heraclitean Society, vol. 17. Western Michigan University, 1994.

Robertson, M. D. "Possibility, Freedom, and Selfhood: Two Accounts". Unpublished, 1994.

Robertson, M. D. "Dualism vs. Materialism: A Response to Paul Churchland", 1995. Posted on Substack, 2023.

In 1995, commenting on a version of this essay, one of my professors suggested that I read C.I. Lewis. 29 years later, in 2024, I finally got around to reading Mind and the World Order, and there are indeed several points of agreement.

I really appreciate the depth of the KT/KH framework—it highlights the interdependence of knowing that and knowing how in a way that traditional epistemology sometimes overlooks. IFEM shares a lot of these concerns but approaches the question from a different angle, particularly when it comes to knowledge refinement.

KT/KH emphasizes how knowledge enables control, while IFEM is more focused on how knowledge stabilizes over time. If KH and KT are interdependent, should we expect certain epistemic structures to persist rather than shift indefinitely? IFEM suggests that by tracking how knowledge reduces uncertainty (or entropy), we can measure when we’re seeing true epistemic refinement versus when we’re just cycling through conceptual frameworks.

I’m also curious how you’d see this playing out in AI. If AI can refine its knowledge without subjective KH, does that mean there’s an alternative form of procedural knowledge at play? Or do you think KH is fundamentally tied to human cognition in a way AI can’t replicate?

Would love to hear your thoughts on whether IFEM’s entropy-reduction framework could complement KT/KH’s model of knowledge as control.