[This is a paper I wrote for a graduate seminar on the philosophy of time in 1994. The original title was

“Review of L. Nathan Oaklander’s Temporal Relations and Temporal Becoming: a Defense of the Russellian Theory of Time”

I’ve added a couple of explanatory footnotes but made no substantial changes.]

In his book Temporal Relations and Temporal Becoming: a Defense of the Russellian Theory of Time (Lanham: University Press of America, 1984), L. Nathan Oaklander surveys the debate within Anglo-American Philosophy during the 20th century regarding the ontology of time, and concludes that the position variously called the “Russellian view”, the “B-theory”, or the “tenseless theory” of time is correct, and that the “McTaggartian view”, the “A-theory”, or the “tensed theory” of time is incorrect. Oaklander also examines the philosophical methodology that has been employed in this debate, and finds fault with the emphasis that has been placed on linguistic analysis.

The problem, as Oaklander sees it, is this: as Oaklander’s title indicates, there are two fundamental issues that an adequate ontology of time must address. First, there is the question of the transitory aspect of time, or temporal becoming. This concerns the ordinary experience of the “flow” of time, as future events become present and then recede into the past. Secondly, there is the question of the static aspect of time, or temporal relations. This concerns the fixed, unchanging relations of earlier than, later than, and simultaneous with that obtain between events.

Our commonsense view of time includes both aspects, but this gives rise to conflicting intuitions. It seems that there is a sense in which only present events are real, but if past and future events are not real, they cannot stand in relation to each other or the present, since only what is real can sustain relations. Also, events can be said to change with respect to the “A-determinations” of pastness, presentness, and futurity, yet they are unchanging with respect to their relations with each other, i.e. the “B-relations” of earlier-than, simultaneous-with, or later-than. Finally, if events are thought of as changing, or as sustaining relations, then events must endure, but it seems that at least some events can also be seen as temporal points having no duration. Oaklander argues that either temporal relations or temporal becoming must be viewed as fundamental, and that whichever of these is not fundamental must be denied ontological status and analyzed in terms of the other.

Oaklander also argues that this analysis must be an ontological analysis, and not merely a linguistic one. Much of the debate has dealt with the question of whether A-statements can be reduced to B-statements or vice versa, but Oaklander disputes the ontological significance of the linguistic question.

A-theorists have maintained that temporal becoming is primary, and have advocated various theories involving absolute becoming, a moving NOW, or the existence of the temporal properties of pastness, presentness, and futurity.

B-theorists, on the other hand, take the temporal relations of earlier-than, later-than, and simultaneous-with to be primary, characterizing these relations as simple, unanalyzable, and asymmetric.

McTaggart’s Paradox

The debate in its current form began with McTaggart’s article, “The Unreality of Time”. Oaklander reconstructs McTaggart’s argument as follows:

If the application of a concept to reality implies contradiction, then that concept cannot be true of reality

Time involves (stands or falls with) the A-series and A-statements. That is, if the A-series (or A-statements) involves a contradiction, then time involves a contradiction.1

The application of the A-series to reality implies a contradiction.

Therefore, neither the A-series nor time can be true of reality. (45) [All page citations refer to Oaklander’s book.]

This argument has shaped the debate because B-theorists do not accept the second premise, and A-theorists reject the third. Oaklander argues that the A-theorists fail to resolve the paradoxes inherent in the idea of absolute becoming, but the B-theorists successfully refute the premise that the existence of time entails the existence of A-determinations.

The A-theory

In chapter 3 of his book, Oaklander examines the A-theories of George Schlesinger, C. D. Broad, Richard Gale, John Wisdom, L. Susan Stebbing, Ferrel Christensen, and A.N. Prior and concludes that none of them satisfactorily resolves McTaggart’s paradox. While Oaklander’s selection of A-theorists is commendably broad, his criticisms of Schlesinger, Broad, and Prior are faulty.

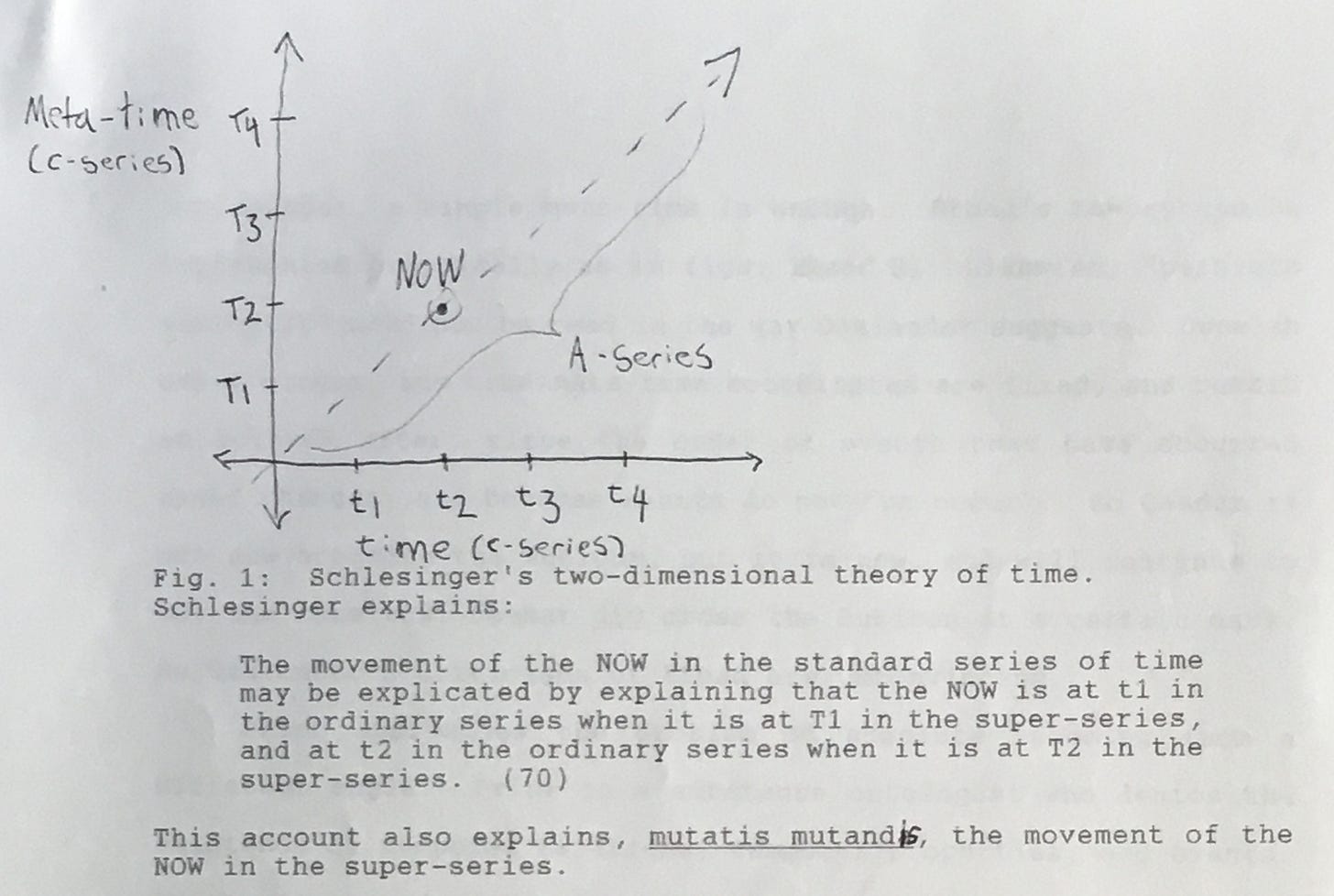

Schlesinger has a “moving NOW” conception of time. He attempts to avoid McTaggart’s paradox by positing a “meta-time” or “super-time” as an additional time-series in which the NOW moves. He does not believe that this leads to an infinite regress, because just as super-time makes time intelligible, time makes super-time intelligible.

Schlesinger’s response to McTaggart’s paradox is as follows:

All the moments of our regular time series co-exist together at each moment of the super-time, and the position of the NOW in regular time varies from moment to moment in super-time. (Moments) in regular time can assume different properties at different moments in super-time. . . . Thus the problem of the extensionlessness of the moments in the continuum of which they form a part is resolved with the introduction of a higher order time continuum in which they have unlimited duration. (qtd. in Oaklander, 71)

Thus Schlesinger proposes a two-dimensional view of time (Figure 1). Schlesinger poses three challenges to critics who do not view this as a satisfactory response to McTaggart’s paradox:

First, it would have to be shown that McTaggart cannot make sense of the changes going on in ordinary time unless he postulates a meta-time of equal richness. That is, a meta-time that admitted B-relations only would not be capable of performing its required function. Secondly, it would have to be shown that in order to explicate the movement of the NOW in meta-time, we could not employ standard time in the same manner we employed meta-time to explicate the movement of the NOW in standard time and therefore we would be forced to introduce a third temporal series. Lastly, it would have to be shown why the regress thus resulting would have to be regarded as vicious. (72)

Oaklander believes he can answer each of these challenges. In response to the first, Oaklander claims that Schlesinger’s view is incompatible with McTaggart’s:

According to McTaggart, you cannot have B-relations between events unless those events have A-determinations and change with respect to them. . . . since a B-series without an A-series is not a temporal series, the second series without becoming does not enable the first series to avoid the incompatible properties problem. (72-73)

But here Oaklander misreads Schlesinger. When Schlesinger says “a meta-time that admitted B-relations only”, he means a B-series without a NOW. But he does not mean a B-series without the NOW. That is, “a meta-time of equal richness” would have its own unique NOW moving along with it, in addition to the NOW of the first temporal series. There is no need for such an entity, and this is what Schlesinger is dispensing with. But Schlesinger is not dispensing with the NOW – the A-series that makes the C-series2 of time a B-series is the same A-series that makes the C-series of meta-time a B-series, as Figure 1 shows. One NOW suffices for both.

Perhaps Schlesinger’s wording is infelicitous in that it gives the impression that time is somehow subordinate to meta-time, when in fact the two are on an equal footing, like length and width, and neither makes sense without the other. But if Schlesinger’s two-dimensional view of time is properly understood, it is immune to Oaklander’s objection. Oaklander’s responses to Schlesinger’s other two challenges are likewise based on this misunderstanding, so I will not address them in further detail.

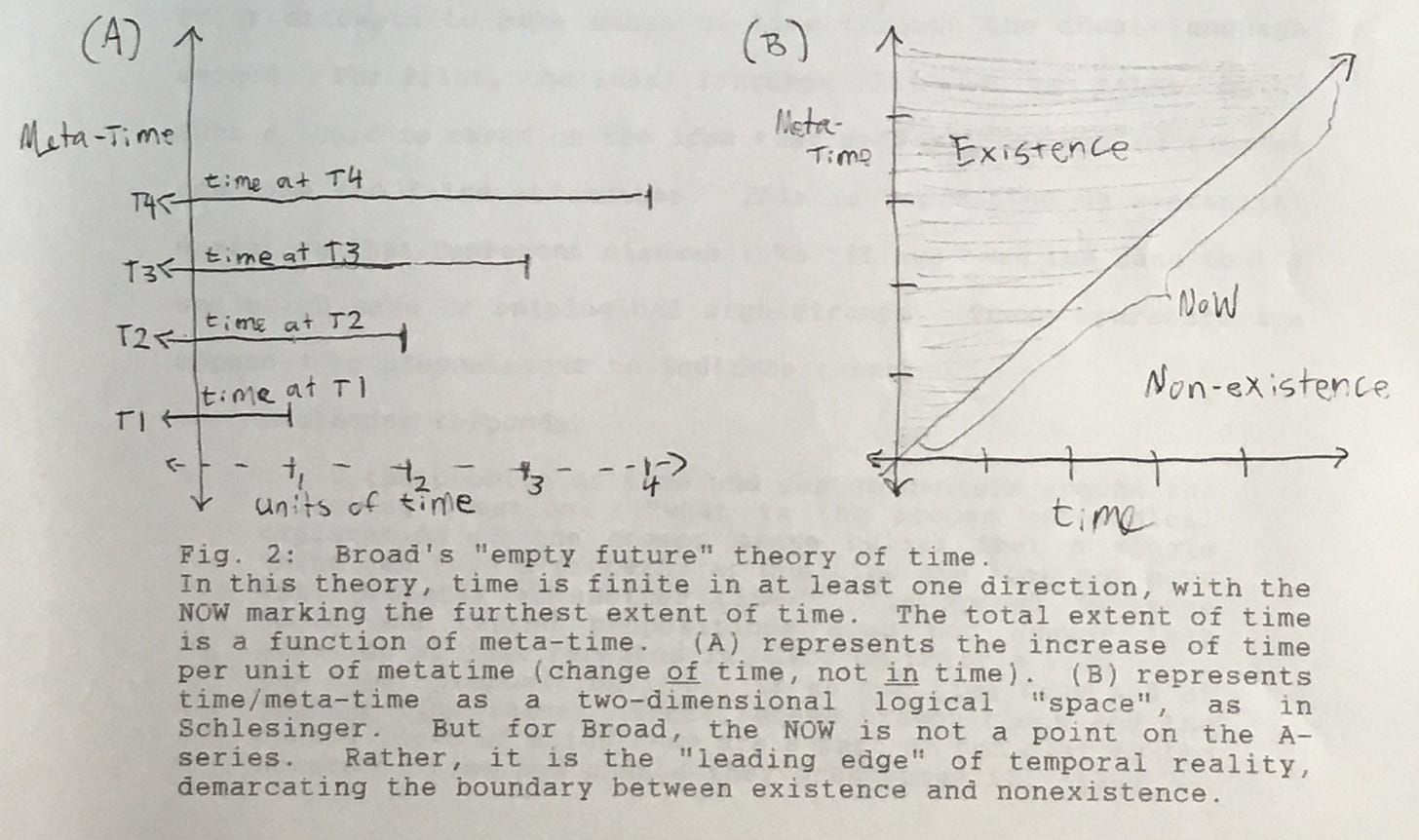

Next Oaklander turns his attention to the A-theory of C.D. Broad, as presented in Scientific Thought, The Mind and its Place in Nature, and Examination of McTaggart’s Philosophy. In Broad’s theory, absolute becoming is fundamental and unanalyzable. The past and present exist, but the future does not. The sum total of existence is constantly increasing. Once an event comes into being it “persists eternally”. The change of events from past to present to future is a change of time, which cannot be reduced to ordinary qualitative change, which is change in time.

Oaklander interprets “persists eternally”to mean that “once an event comes into existence it continues to exist at every moment thereafter”; but this cannot be true, for “Caesar is not now crossing the Rubicon!” Oaklander also says,

Unfortunately Broad’s talk about the sum total of reality continually increasing with the fresh becoming of events leads to the infinite regress that he sought to avoid. For the sum total of reality is always changing. At one moment, it includes a certain number of existents and then at a later moment it includes a greater number of existents. But with becoming and time being essential to each other the members of the series of moments at which the sum total of existents is x, and then y, must themselves undergo becoming which requires a second series of moments and so on. (87)

But Broad’s views do not require an infinite series. As with Schlesinger, a single meta-time is enough. Broad’s theory can be represented graphically as in figures 2 (A) and (B). Likewise, “persists eternally” need not be read in the way Oaklander suggests. Once an event occurs, its time/meta-time coordinates are fixed, and remain so forever after, since the order of events that have occurred never changes, and because events do not “un-occur”. So Caesar is not now crossing the Rubicon, but it is now, and will continue to be, the case that Caesar did cross the Rubicon at a certain date. So Oaklander’s criticisms of Broad are unconvincing.

A. N. Prior approaches the problem of absolute becoming from a different angle. Prior is a substance ontologist who denies the existence of temporal relations, temporal properties, and events. Prior attempts to make sense of time through the ideal-language method. For Prior, the ideal language (IL) involves tense logic. Such a logic is based on the idea that propositions can be true at one time and false at another. This is represented by sentential operators that represent clauses like “It has been the case that”, and which have no ontological significance. These operators are appended to propositions to indicate tense.

Oaklander responds,

. . . the problem of time and change centers around the following question: “what is the proper ontological explanation of the common sense belief that a single thing can have a property at one time and then not have that property at another time?”. The appeal to tense logic and tensed properties does not answer that question it just reraises it. For on Prior’s view . . . the same proposition . . . is at one time true and at another time false. Thus, tensed propositions and the tensed logic of which they are a part do not clarify the nature of time and change[,] they presuppose it. (96)

But tense logic does answer Oaklander’s question. The “proper ontological significance” of our beliefs about time, according to Prior, is that time is neither a particular, nor a substance, nor a property or a relation of a substance; time is a set of purely logical relations between propositions. Perhaps Oaklander wants to insist that time is a descriptive feature of the world, as opposed to a logical one, but he gives no argument to support this view.

As for the presuppositions of tense logic, Oaklander fails to grasp that this is not a criticism of tense logic in particular, it is in fact a criticism of the ideal-language method in general. The failure of attempts to formulate a satisfactory “free logic” suffice to prove that no ideal language is devoid of metaphysical presuppositions. Just as quantificational logic presupposes that (a) something exists, and (b) existence is not a descriptive feature of the world, tense logic presupposes that (a) something becomes, and (b) becoming is not a descriptive feature of the world. If Oaklander finds presuppositions of this nature unacceptable, then he should reject the ideal-language method. But that does not count against the A-theory as such, it merely rules out one method of explicating it. In light of Oaklander’s criticism of analysis in chapter 4 of his book, it is odd that Oaklander should make such a confusion.

But Oaklander has other criticisms of Prior. Like Broad, Prior denies that becoming is the same sort of phenomenon as qualitative change. Prior claims that only existing substances can undergo alteration. Prior interprets statements about substances that do not yet exist, or that no longer exist, as expressing general facts, and not singular facts. Thus, a statement like “the warehouse burned down” is not a singular statement about a currently existing substance, it is a general statement.

Oaklander finds this unclear. Oaklander takes Prior to be using the distinction between singular and general statements to explicate the notion of becoming. Oaklander thinks this may mean that becoming is the alteration of facts from general to particular or from particular to general. But this notion of facts changing is no clearer than the notion of individuals becoming.

It is not clear that this is Prior’s intent. It seems more likely that Prior, again like Broad, takes becoming to be unanalyzable, hence the introduction of operators whose sole function is to represent becoming.

But Oaklander ultimately succeeds in casting doubt on Prior’s treatment of time:

The point to be emphasized is that Prior cannot consistently treat propositional prefixes such as “it will be the case that” and “it has been the case that” as operators without ontological significance. . . . in laying out the semantics of tense logic, Prior says “that the future-tense statement ‘professor Carnap will be flying to the moon’ is true if and only if the present tense statement will be true” and as L. J. Cohen has said, “these temporal truth-evaluations in the sentences expressing his semantic rules cannot be mere operators.” Thus, it appears that tensed propositions and tensed facts are temporal facts, that is, they exist in time, and that temporal operators are properties that such “facts” possess. At this point, the specter of McTaggart raises its ugly head . . . (102)

Analysis and Time

Next Oaklander turns his attention to the role that linguistic analysis has played in the debate between A-theorists and B-theorists. At the center of this debate is the question of whether tensed sentences can be reduced to tenseless ones and vice versa. The parties to this debate have assumed that the resolution of the syntactic and semantic issues involved in such a reduction would also resolve the ontological issue. Oaklander denies this.

Oaklander maintains that the ideal-language method of analysis cannot in principle resolve the ontological issue, because no ideal language can perspicuously represent (1) everything that can be said in natural language, and (2) all that exists.

Oaklander uses the example, “(A) is present and nothing is simultaneous with it” to prove his point. Given that B-theorists define presentness in terms of simultaneity, the transcription of (A) in the B-theorists’ IL is contradictory. Oaklander asserts that this does not invalidate the B-theory of time, it merely shows that the B-theorists’ ontological analysis cannot also represent the logic of ordinary language. Conversely, the A-theorists’ transcription of (A) represents the logic of ordinary language, but is either paradoxical or circular with respect to the ontological issue, for, since it involves presuppositions that change truth values, the A-theorists must presuppose an account of time.

Oaklander argues that this impasse results from the assumption that an IL that resolves the logical issue also resolves the ontological issue, and vice versa. Oaklander denies this, and asserts that the issue of translatability pertains to the logical issue and has no bearing on the ontological issue.

The B-theory

Oaklander devotes three chapters to a defense of the B-theory.

Oaklander summarizes the B-theory thusly:

The most fundamental aspect of the Russellian view, as I understand it, is that temporal relations are simple, unanalyzable, and irreducible. Thus, the Russellian maintains that (i) an adequate ontology of time requires temporal relations (between particulars), and that temporal properties and/or temporal individuals alone will not do. . . . (ii) temporal relations do not require that their relata have temporal properties. . . . (iii) there are no non-relational temporal properties of pastness, presentness,and futurity. . . . (140)

According to this view, “present” or “now” is simply an indexical that indicates a certain time; when someone says, e.g., “It’s raining now” at time t1, “now” means “at time t1”. Future and past tenses are likewise defined relative to the time of utterance (or writing or thought or whatever).

In support of McTaggart’s claim that a complete theory of time requires A-determinations, critics have found the following flaws with the B-theory: it does not account for our different attitudes regarding the past and the future, it “spatializes” time, it makes reality a “block universe” or totum simul, and it implies fatalism.

Oaklander begins his defense of the B-theory by addressing the claim that the B-theory is unable to account for our sense of the flow of time. Oaklander attempts to account for our experience of time’s “movement” or passage or flow, as indicated by such feelings as anticipation or nostalgia, in this way:

There is a certain event e . . . that occurs (tenselessly) at tn. At say t1, I wish it was now tn. . . . Then, at a later time t2, I wish . . . the same thing. Finally, suppose, at tn . . . I experience (event e). The Russellian would say, as would everyone else, that time (event e) moved from the future to the present. The truth that underlies that vague statement would, however, be the following: my wish (anticipation) . . . occurs timelessly at t1 and the event that I wish to occur is later than t1. At t2, my wish or utterance occurs (tenselessly), but the temporal span (duration) between t2 and tn is less than the temporal span between t1 and tn. Finally, at tn, the experience of joy occurs (tenselessly) and so does the event e that I have been anticipating at t1 and t2.

But this does not describe movement. It describes a set of particulars and a set of relations among particulars. Movement in the sense meant by A-theorists, and by ordinary usage, involves continuants (albeit ontologically primitive continuants in the first case and commonsense continuants in the other), not collections of partculars. Oaklander’s Parmenidean redefinition of the flow of time amounts to a dismissal of our ordinary experience as illusory. Such a dismissal may be consistent, but if Oaklander chooses to go that route, then he should call a spade a spade and not pretend to be articulating a theory that validates our ordinary experience.

Furthermore, the fact that we feel anticipation or dread before an event and nostalgia or relief afterwards becomes purely arbitrary and irrational on Oaklander’s account. For this view does not account for the directionality of time, nor does it account for the qualitative difference between the future and the past that we take for granted in ordinary experience, and hence does not account for different attitudes toward the future and the past.

In responding to the latter criticisms, Oaklander accuses his critics of begging the question by insisting on their definition of change (147), and again relies on his redefinition of movement to deflect criticism. But whatever the limits of conceptual analysis may be, this much is clear: movement as such implies continuants. Oaklander’s opponents are not begging the question by insisting on this; the fallacy at work here is Oaklander’s equivocal use of “movement”.

Oaklander’s defense of the B-theory from the “spatialization” objection also fails.

As philosophers have become more familiar with the results of relativity theory, many B-theorists have found Minkowski’s four-dimensional spacetime view of reality appealing. Critics have charged that B-theorists that represent reality in this way “spatialize” time, or explicate time in a way that makes it indistinguishable from space.

Oaklander responds,

Succession in time and “succession” or “in front of” in space are experienced as different relations. We all know that they are different although we cannot say in what respect they differ. But perhaps that is because they are ontologically simple entities that are just different. (175)

If the question were how to distinguish length from width, then such a response might be adequate. But in this context such a response is at best evasive. For we can say in what respects they differ: there is the unidirectionality of time (simply labeling the earlier than relation “asymmetrical” does not account for this), the indeterminacy (or at least epistemic inaccessibility) of the future, and the fact that an object can occupy one volume of space at two times but cannot occupy two volumes of space at one time.

The “block universe” criticism and the fatalism objection go hand-in-hand. Critics have charged that the four-dimensional view of time and space entails that all events “coexist eternally”. This in turn entails fatalism. Oaklander rightly regards this as the most serious objection to the B-theory.

Oaklander’s response to Aristotle’s classic “sea-fight” argument, and to modern elaborations upon it by Cahn, Łukasiewicz, and others, is to claim that his opponents “unacceptably assume that the true facts correspond to facts (or truths) that exist in time, and that what exists is present” (205).

Oaklander rejects these assumptions because he views temporal relations as universals that are not themselves in time.

. . . the fact in virtue of which that proposition [that there will be a sea-fight] is true is that a sea-fight occurs (tenselessly) later than t1. However, that state of affairs does not exist at the time at which the future tense proposition is uttered . . . Indeed, it does not exist in time at all. For the Russellian, states of affairs which contain temporal relations between events are eternal in the sense of existing outside the network of temporal relations, but not in the sense of existing (or persisting) throughout all of time. Consequently, the present truth of a future tense proposition does not imply that the state of affairs in virtue of which it is true “pre-exists” in the present . . . (205)

Thus the sea-fight is in time, and our utterance about it is in time, but the relation between the utterance and the sea-fight is not in time.

But this does not defeat the fatalism objection. Firstly, Aristotle did not assume that propositions had to correspond to facts in time (see Physics). But in any case Oaklander’s entire argument is a red herring. If all future events are determinate in any sense, including timelessly determinate, then free will is impossible. Whether it is timelessly true that Oedipus will marry his mother or merely true now that Oedipus will marry his mother makes no difference; in either case, Oedipus’s deliberations with regard to this event are meaningless -- his destiny is fixed.

The relevance of temporal theory to free will can be illustrated metaphorically in this way: If Oaklander’s view is correct, then life is like a scripted play. The fact that the script itself is not part of the action does not alter the fact that the outcome of the play is preordained. But if there is absolute becoming, then it is possible that life is like a piece of improvisational theater, in which the events unfold according to the choices of the actors.

Conclusion

Oaklander believes he has proven three things: (1) that the A-theory is unable to avoid McTaggart’s paradox, (2) that linguistic analysis cannot answer the question of the ontological status of time, and (3) that the B-theory, properly understood, does not have the problems that are usually associated with it.

With regard to (1), Oaklander fails to refute the theories of two A-theorists, namely Schlesinger and Broad.

Concerning (2), Oaklander is right that this sort of analysis, or any other sort of linguistic or conceptual or semantic analysis, cannot show how things are. But it can show how things must be if certain conditions are met. The A-theorists have shown that the sort of change that allows free will and validates our ordinary experiences of movement and passage requires absolute becoming. This does not prove that there is is absolute becoming, but it does prove that any advocate of the B-theory has some bullets to bite. If Oaklander is unwilling to bite those bullets, then he should give up the B-theory.

Oaklander refuses to recognize this dilemma. Unfortunately he does not show how a B-theorist can avoid these problems, for his arguments for (3) suffer from various flaws.

Thus, while Oaklander’s book provides a useful overview of the issues, positions, and methods involved in this debate, it will not be the last word on the subject.

[ It wasn’t Oaklander’s last word on the subject, either. He wrote or edited several more works about the philosophy of time after this. L. Nathan Oaklander’s PhilPeople page ]

A bit more about the supposed contradiction premise 3 is talking about:

McTaggart’s argument (often called McTaggart’s paradox) that the notion of the A-series involves a contradiction goes as follows. The first step is to note that the A-characteristics of pastness, presentness and futurity are incompatible with each other. Nothing can exemplify more than one of these characteristics. The next step is to consider the effect on that fact of the other aspect of an A-theoretic conception of time, namely, the fact that time is dynamic, so that what is future becomes present and then becomes past. When the flow of time is added to the picture, we find that, since events are continually changing their A-series locations, each one exemplifies every A-characteristic. But this is in direct conflict with the first step, that nothing can exemplify more than one A-characteristic.

Routledge Encylopedia of Philosophy, “Time, metaphysics of, Sec. 6: McTaggart’s Paradox”)

More about the C-series:

As the application of the A series to reality involves a contradiction, the A series cannot be true of reality. This does not entail that our perceptions are false; on the contrary, McTaggart maintains that it is possible that the realities which we perceive as events in a time series do really form a non-temporal C series. Although this C series would not admit of time or change, it does admit of order. For example, if we perceive two events M and N as occurring at the same time, it may be that ─ while time does not exist ─ M and N have the same position in the ordering of the C series. McTaggart attributes this view of time to Hegel, claiming that Hegel regards the time series as a distorted reflexion of something in the real nature of the timeless reality. In “The Unreality of Time”, McTaggart does not consider at length what the C series is; he merely suggests that the positions within it may be ultimate facts or that they are determined by varying quantities within objects.

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart (1866—1925), sec. c, The Unreality of Time”