Readers who are unacquainted with Jean-Paul Sartre’s work may find Part 1 of this essay hard to follow. For a short overview of the part of Sartre’s work that this essay addresses, I recommend section 4.1 of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s entry on Sartre.

Jean-Paul Sartre explores the interconnections between possibility, freedom, and selfhood in several of his works, most fully in Being and Nothingness. While Sartre's account is an improvement over earlier theories, it contains certain missteps. I shall attempt to articulate an alternative approach.

1. Sartre on Possibility

Sartre examines the notion of possibility in Part Two, Chapter IV of Being and Nothingness (all quotes from Hazel E. Barnes's translation, Washington Square Press edition, 1966). Sartre takes the usual construal (that is, the usual post-Leibnizean philosophical construal) of "possible" to mean "an event which is not engaged in an existing causal series such that the event can be surely determined and which involves no contradiction either with itself or with the system under consideration" (148).

Sartre claims that this renders the question of possibility a question of knowledge. So conceived, possibility becomes subjective and representational, a merely logical relation among certain thoughts. But Sartre rejects this understanding of possibility, for it does not account for the role that the notion plays in ordinary experience, in which possibility is given as an objective feature of the world that is independent of subjective representation.

The possible appears to us as a property of beings. After glancing at the sky I state, "It is possible that it may rain." [. . .] This possible belongs to the sky as a threat; it represents a surpassing on the part of these clouds, which I perceive, toward rain. The clouds carry this surpassing within themselves [. . .] The possibility here is given as belonging to a particular being for which it is a power. (149)

This everyday understanding of possibility would seem to accord with the Aristotelean concept of potentiality. But Sartre rejects this view also. For such a view would make possibility a feature of being-in-itself. Sartre asserts that being-in-itself "is what it is"; clouds in themselves are simply clouds, not "potential rain". It is only in connection with human reality that clouds acquire the character of the possibility of rain. Thus it must be through the for-itself that possibility comes to the world. Thus this is another instance of a recurring theme in Sartre's work, namely, the inadequacy of the real/ideal dichotomy. Possibility cannot be a real feature of the in-itself, for the in-itself simply is what it is, in full actuality. Nor can possibility be ideal, because no purely subjective or conception of possibility can account for our experience of it.

The issue can also be seen in light of the traditional distinction between de dicto and de re conceptions of possibility.

Sartre rejects both. De dicto is unacceptable:

If we then define possible as non-contradictory, it can have being only as the thought of a being prior to the real world or prior to the pure consciousness of the world such as it is. In either case the possible loses its nature as possible and is reabsorbed in the subjective being of the representation. (149)

But de re is also unacceptable because

[. . .] this would be be to fall from Charybdis to Scylla, to avoid the purely logical conception of possibility only to fall into a magical conception (150).

Sartre believes he can avoid these dilemmas by appealing to his notion of lack. The for-itself is its own lack; this grounds the being of possibility. Just as the for-itself is its own lack, it is its own possibility. For it is only through lack that possibility arises, for the fulfillment of the lacked is the only event that can be properly thought of in terms of possibility.

The lacked is an objective feature of the world; it is a real absence. But absence comes to the world through the nihilating activity of the for-itself. Thus possibility, which arises from lack, is an aspect of human reality, yet is not subjective.

But this account of possibility is unsatisfactory as it stands. The possible is the attainment of the lacked. But the attainment of the lacked would result in the realization of the ideal self, which Sartre says is impossible. Thus the possible is the impossible.

Furthermore, Sartre does not explain the basis for the boundaries of the possible as we experience it. The lacked is a particular concrete reality. But we experience the possible as a range of experiential outcomes (ranging from highly unlikely to almost certain to occur), not a single particular reality.

Perhaps these considerations motivate the elaborations of the theory of possibility that appear in Part Three, Chapter 3.

The possibility that consciousness exists non-thetically as consciousness (of) being able not to not-be this is revealed as the potentiality of the this of being what it is (266). [. . .] Those potentialities which refer back to the this without being made to be by it and without having to be—those we shall call probabilities to indicate that they exist in the mode of being of the in-itself (270-271).

But by characterizing probability in this way Sartre reintroduces an understanding of possibility that he had earlier rejected, namely the view that possibility is a characteristic of the in-itself. His use of potentiality in this context similarly recalls the Aristotelean view that Sartre had earlier dismissed as "magical".

In light of this apparent discrepancy, a closer examination of Sartre's arguments against possibility as a mode of being that is independent of human reality (that is, de re) is in order.

If the possible can in fact come into the world only through a being which is its own possibility, this is because the in-itself, being by nature what it is, cannot "have" possibilities. The relation of the in-itself to a possibility can be established only externally by a being which stands facing possibilities. The possibility of being stopped by a fold in the cloth belongs neither to the billiard ball which rolls nor to the cloth; it can arise only in the organization into a system of the ball and the cloth by a being which has a comprehension of possibles. But since this comprehension can neither come to it from without—i.e., from the in-itself—nor be limited to being a thought as the subjective mode of consciousness, it must coincide with the objective structure of the being which comprehends its possibles. (152)

This argument is utterly unconvincing. It merely asserts and reasserts that possibility cannot belong to being-in-itself, without giving any reason why this is so. Likewise, the premise that possibility requires "comprehension" is an additional assumption that may be rejected, using Sartre's own arguments against idealism for support.

With these considerations in mind I will now outline an alternative understanding of possibility that is based on the Aristotelean conception of potentiality that Sartre explicitly rejects but implicitly accepts.

2. Possibility: Another Approach

In his examination of the everyday understanding of possibility, Sartre notes,

The possibility here is given as belonging to a particular being for which it is a power. This fact is sufficiently indicated by the way in which we say indifferently of a friend for whom we are waiting, it is possible that he may come" or "he can come." (149)

I would like to expand on this insight. Consider the following statements:

(1) "Al could have joined the army."

(2) "Al could have been female."

(3) "Al could have had a heart attack."

(4) "It could have rained yesterday."

(5) "The sky could have been purple with green polka dots."

All of these counterfactuals can be restated in terms of possible worlds. But to do so glosses over significant intensional differences between them. (1)-(3) all have Al as the grammatical subject, but (1) seems to ascribe something (a power) to Al in away that (2) and (3) do not. (5) asserts a bare logical possibility but the others assert possibilities which somehow seem closer to being realized. Possible worlds semantics fails to capture these distinctions. Sartre's explication shows some appreciation of the nuances involved here but has the shortcomings noted above. I shall attempt to explicate the nature of possibility in a way that takes these distinctions into account.

2.1 Levels, Laws, and Modes

The principle of non-contradiction (PNC) is sometimes taken to be a normative principle concerning propositions. Sartre seems to take such a view of it in the passages quoted above; elsewhere he claims it has only "regional" application (see Salvan, 1962; also cf. Slater, 1988). I take it to be a descriptive principle concerning the nature of being. This is easier to accept when PNC is formulated as the law of excluded middle (XM). Nothing can be and not be in the same way at the same time. That's just how being works, so to speak.

This law delineates what is possible for beings qua beings simpliciter. The laws of physics further circumscribe what is possible for beings qua physical beings. If biology, psychology, etc. are irreducible to physics, then the laws of those sciences still further limit what is possible for beings that are living, mentally endowed, etc. If these sciences are reducible to physics then their laws are elaborations of physical laws and have no additional bearing on the question of possibility. Thus the laws that regulate each level of being successively narrow the range of what is possible (cf. Auguste Comte’s idea of the hierarchy of the sciences). In this context, "the laws of those sciences" means "the laws that apply specifically to the subject matters of those sciences, whether or not those laws are discoverable".

Every mode of being is a locus of possibility, and vice versa. By "mode of being" I mean any existent that cannot be reduced to any combination of other existents, be it a substance or particular or relation or whatever. Modes of being are individuated by the possibilities of which they are the loci. "Level of being" refers to the generality of the laws that govern one or more modes, with "lower" levels having greater generality. There may be only one mode of being at a particular level or there may be several, but if there are several they will all be of the same type. Modes of being of higher levels are ontologically dependent on modes of all lower levels. Within this general schema competing metaphysical theories may offer different analyses of the number and kinds of levels and modes that exist, with more reductivist ontologies having fewer levels and less pluralistic ontologies having fewer modes than their respective opponents.

To clarify matters I shall offer some examples of ontologies based on this framework. The first is loosely based on the early Marx, and has four levels of being, beginning with the "metaphysical" level of being, which is governed solely by PNC/XM, and at which there is only one mode of being, namely that of Being simpliciter. The next level is the "physical" level of being, which is governed by PNC/XM and by the laws of a hypothetical unified physical science, including quantum mechanics, relativity theory, and facts concerning the boundary conditions of the universe. At this level there is again only one mode of being, namely matter/energy/spacetime ("matter" for short). Next comes the biological level, at which there are a great number of modes, all belonging to the type, "species", and governed by the respective laws of "species being" of each. Thus there is horizontal differentiation as well as vertical. Finally there is the "social" level of being, whose modes are social classes, and which is governed by the laws of the historical dialectic. The laws of these four levels jointly constrain possibility.

Variations may easily be conceived. According to a vitalist interpretation of biology, there would be only one mode at the biological level, namely "life" or the "life force" or whatever.

An alternative understanding of the social level might deny that this level is governed by historical dialectic and instead posit the following: the social level is governed by the laws of a hypothetical unified social science, which includes anthropology, sociology, etc. At this level the modes of being are cultures (or maybe societies), of which there are several instances. Note that it is not the case that "culture" is the single mode of being at this level; rather, there are several numerically distinct modes of which "culture" is the type. Distinct cultures are all constrained by the same laws from previous levels (PNC/XM and physical laws) but each supplements these constraints with its own unique laws the laws of "French-ness" are different from the laws of "Maori-ness" (cultural universals, if there are any, are presumably determined by species being).

More radical departures are also possible. A follower of E. O. Wilson might posit only three levels: the metaphysical, the physical, and the "sociobiological". The latter would have "organisms" as modes, and would have laws based on evolutionary theory. A reductive physicalist would posit only the metaphysical and the physical1. Finally, a radical monist would posit a single level and a single mode of being, and would claim that all the laws of all the sciences are somehow logically necessary.

2.2 Counterfactuals

The laws of various levels constrain our experience of possibilities. But what are possibilities?

Possibility is a genus of second order properties, that is, possibles are properties of properties. Its species are the physically possible, the biologically possible, etc. All possibles are actual in some sense. There are non-actual possibles but only in an equivocal sense, e.g., there are logical possibilities that are physically non-actualized, but there are no logical possibilities that are logically non-actualized. But possibility and actuality are not identical, for what is actual at any level is possible at every level; the physically actual is logically, physically and biologically possible.

Thus Sartre is correct in rejecting definition of possibility strictly in terms of logical non-contradiction, but only because there are other laws besides PNC/XM that constrain reality. Sartre also fails to grasp the de re metaphysical import of PNC/XM.

Insofar as possibles are experienced, possibles are further divided into the factual and the counterfactual. Some thinkers have suggested that fictitious entities like centaurs might exist in some sense, e.g., as intentional objects. Others have dismissed the question out of hand. I suggest that inquiring into the ontological status of counterfactual entities is a poorly formed question; counterfactuals are actual properties of actually existing entities, i.e., modes of being. Al could have been female, but it is incorrect to ask whether or in what sense this woman that Al could have been exists; rather, could-have-been-born-female is an actual property that Al now possesses by way of PNC/XM (this example is somewhat misleading; I shall clarify it shortly).

Counterfactuality and actuality are not mutually exclusive; rather, it is counterfactuality and factuality that are mutually exclusive. That the property of being female is counterfactual for Al and not factual is due to the various laws of biology, physics, etc. It should be noted that such properties are not mind-dependent.

Possibles, whether counterfactual or factual, are properties of properties of the irreducible modes of being that exist at the various levels of being. Bare logical possibilities are (second order) properties of unqualified Being; physical possibilities are properties of matter/energy/spacetime; if biology is irreducible than biological possibilities are properties of life; psychology, mind; anthropology, cultures (severally); etc. So, to clarify the earlier example: strictly speaking, we should not say that "Al could have been female" means that could-have-been-female is one of Al's properties; rather, that Al could have been female is a second-order property of matter, or of life, whichever is taken to be the relevant level of being at which the property is rendered counterfactual. The property accrues to the modes that exist at the constraining level: that Al could have been female is a bare logical possibility that is rendered counterfactual by physical or biological laws, hence it is a property of matter or life.

3. Freedom and Selfhood

None of the sample ontologies I considered above posited persons as irreducible modes, nor has there been any mention of freedom in the discussion so far. The defender of the Sartrean conception of possibility might rightly demand at this point that I explain how my theory of possibility can account for human reality.

It would be a mistake to suppose that the framework I have been elaborating here implies determinism. I have characterized laws in terms of constraint, not determination. When one thing determines another, given the way the first thing is, there is one and only one way the second can be. Constraint is less restrictive than determination. When one thing constrains another, given the way the first thing is, there is at least one way the second thing cannot (factually) be, such that the second thing could have been that way in the absence of that constraint. Thus each level of laws adds constraints on the ways that modes of being can be, successively ruling out possibilities that are allowed by earlier levels. But there is nothing in this to suggest that when the laws are summed, only one possibility will be open to each mode.

If in fact multiple possibilities are open to certain modes, then the question arises as to what makes some of these possibilities factual and others counterfactual. In some cases it may be in principle inexplicable; there may be a certain amount of randomness in the universe. But this of course does not give us freedom. In keeping with agent-causal theories of free will I shall posit the agent as that which renders the final determination of possibilities that pertain to the acts of free and conscious beings.

But how do agents figure in my framework? Are agents modes, laws, or levels? One possible answer might be to posit a "personal" level of being which has agents as modes. What then are the laws of the personal level? The personal level is governed by the law of agency, which simply means that agents' choices determine their acts. Since there are no laws of "John-ness" or "Jane-ness", the free choices of each agent function in place of laws for this level of being and also serve to individuate the modes of being that exist at this level. But unlike laws these choices are spontaneous creatio ex nihilo, as Sartre observed. What then prevents the choices of agents from being merely random?

Random means unpatterned. The choices of agents follow a pattern, hence they are not random. But the pattern these choices follow is related to the ends they are directed at, not the causes that produce them. Thus, the pattern that makes each agent's existence unique is self-generated; the ends agents freely choose constitute the patterns that give unity to the narratives of their existence.

Nor are agents' choices of ends random. Patterns, and hence randomness, can only apply to unities with more than one element. A single choice, divorced from its relationship to its consequences, other choices, and everything else, cannot be described as either random or non-random; the concept simply does not apply. Assuming agents choose more than once, then the search for a pattern must be conducted at the holistic level: that is, it is the sum total of an agent's choices which will have a pattern. If agents choose only once, then the basis for evaluation should arguably be the relationship between the choice and the acts that follow from it, which will clearly exhibit a pattern. Hence, free agency does not imply randomness (for more on free will and randomness, see Van Inwagen vs. Van Inwagen on Freedom and Randomness).

Returning to the examples, compare (2) "Al could have been female" with (1) "Al could have joined the army". If reductive physicalism is true and matter is the highest mode, then persons are reducible to physical substances and processes, and both (1) and (2) are ascribing properties to matter. If the individual person or agent is irreducible, then (2) ascribes a property to matter as before but (1) ascribes a property to Al. Whereas physical laws render Al's femaleness counterfactual, if Al's personhood is an irreducible mode of being and locus of possibility then Al renders his military service counterfactual. Since there are no laws of "Al-ness", Al renders his military service counterfactual through his own free choice. It should be noted that the latter account is in accordance with our intuition that (1), but not (2), says something about some kind of ability that is intrinsic to Al.

But applying agency theory in this way is curious from a dialectical point of view. The agent as I have characterized it is clearly identifiable with the willing self of dualistic philosophy. Sartre believed he had to abolish the willing self as an inhabitant of consciousness in order to establish freedom. My account seems to require the willing self in order to establish freedom. Can these accounts be reconciled, or can one of them be eliminated? The key may be the phrase "as an inhabitant of consciousness". For although my account requires the willing self, it does not require the willing self to "inhabit" consciousness.

4. Consciousness and Dynamic Complexity

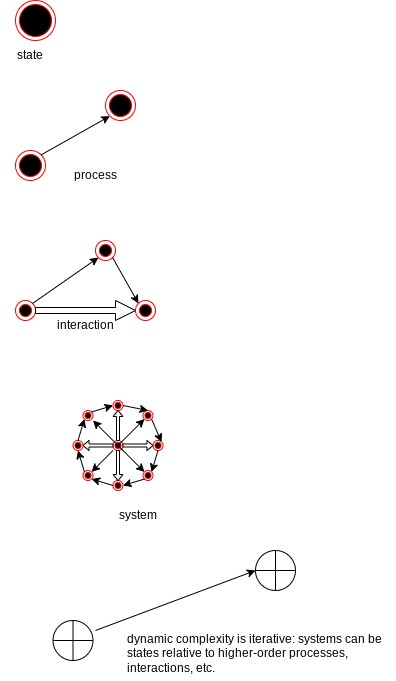

Freedom entails acts, and acts entail change. All changes are relations which fall into one of the following four levels of dynamic complexity: states, processes, interactions, and systems.

State is the limiting case, for it signifies the absence of change (absolutely or relatively). A process is a successive conjunction of functionally related states (i.e., prior states are inputs to a function that yields posterior states as outputs). An interaction is a conjunction of processes that produces a new state or process. A system is a conjunction of interactions that produces a state.

Sartre's account of consciousness is an improvement over earlier accounts because earlier accounts made consciousness a state. Sartre makes consciousness into a process: consciousness is consciousness of something (or the lack of something). The nihilating activity of consciousness happens to being; it is not a state of being.

But this is not enough. For consciousness as a process is separated from other processes. Each consciousness (of) is a whole unto itself. Sartrean consciousness is basically a Humean bundle of such processes, and as such it falls victim to the Kantian criticism of the inability of such a bundle theory to account for the unity of apperception.

Kant and Husserl addressed this problem by positing the transcendent self. Sartre rejected this solution, supposing that the transcendent self would have a fixed (static) nature, thereby denying freedom. But Sartre's attempts to ground the unity of apperception implicitly acknowledge the need for such an entity. For Sartre cannot make sense of freedom or selfhood without employing concepts like ends, purposes, and instrumentality (nor can I). But ends do not exist independently, nor do the acts that are directed at those ends suffice to ground those ends' existence. Just as agents and acts require ends, ends require agents and acts. Intentionality requires an intender as well as an intended. Sartre acknowledges this when he says, "everything which is lacking is a lacking to _____ for _____" (138). Consciousness is not simply consciousness of something, it is someone’s consciousness of something.

Consciousness requires a self, and it requires this self to be a concrete existent and not merely an impossible ideal. Sartre goes to great lengths to avoid this. In Sartre's hands, the I think of the cogito becomes simply, thought occurs. But Sartre can do this only by abrogating the law of non-contradiction. Sartre presumably takes this drastic step because he believes it is the only way to avoid a static self that denies freedom. But I have shown above that this is not necessary. The transcendent self is an agent, and agents are free; they are not determined by their nature because it is their nature to be free.

Sartre makes this mistake because he does not grasp the level of complexity of the relations involving self and consciousness, although he comes closer to grasping it than his predecessors. Sartre understood that consciousness is not a state. But neither is it a process. Consciousness is an interaction between the self and all that is not the self. Agency depends upon consciousness because although agents are free to choose, they must choose from among the options that they perceive, imagine, or conceive.

5. Conclusion

Sartre refuses to dismiss or explain away the freedom that characterizes human reality. On the contrary, he maintains it at all costs, discarding the transcendent self as an entity and curtailing the law of non-contradiction in the belief that these concepts entail the denial of freedom. But the price of freedom is not as high as Sartre believes. A proper understanding of the metaphysical import of the law of non-contradiction coupled with an appreciation of the level of complexity involved in conscious relations shows that freedom is not threatened by the transcendent self or the law of non-contradiction. On the contrary, freedom requires the self, and both can be integrated into a framework based on the law of non-contradiction and de re possibility. Such an approach not only clarifies the connections between freedom, selfhood, and possibility, it validates our everyday experience of these phenomena. On that basis I suggest that is preferable to Sartre's approach.

Bibliography

Danto, Arthur. Jean Paul Sartre. New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Sartre, Jean Paul. Being and Nothingness. Hazel E. Barnes, tr. New York: Washington Square Press, 1966.

Slater, B.H. “Contradiction and Freedom”. Philosophy, Vol. 63, No. 245 (Jul., 1988), pp. 317-330.

Salvan, Jacques. To Be and Not To Be. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1962.

I’ve left out mathematics to simplify this exposition. If mathematics is not reducible to logic, then a mathematical level would occur between the metaphysical and physical. If realism about mathematical objects is true, then they would be modes at the mathematical level.