Aftershock is Robert Reich’s analysis of the 2008 crash for a lay audience. Written in 2010, Reich’s thesis is

[…] the Great Recession was but the latest and largest outgrowth of an increasingly distorted distribution of income, and […] we will have to choose, inevitably, between deepening discontent (and its ever nastier politics) and fundamental social and economic reform. (p5)

Reich’s macroeconomic picture complements Elizabeth Warren’s examination of middle-class financial decisions during the same period (see my previous post). Robert Reich is currently offering free access to his class on wealth and inequality via Substack.

The book has three parts. In Part 1, “The Broken Bargain”, Reich surveys US economic history from the end of the Gilded Age to 2008 and shows how the lessons learned from the Great Depression led to a “basic bargain”. Policymakers realized that

[…] government should […] maintain aggregate demand so that the productive capacity of an economy doesn’t outrun the ability of ordinary people to buy, which would give businesses less incentive to invest. Equally important, enforce a basic bargain giving workers a proportionate share of the fruits of economic growth. The two went hand in glove. When the basic bargain is maintained, the entire economy is balanced. When the basic bargain breaks down, government must step in to reinforce it, or the economy will shrink.

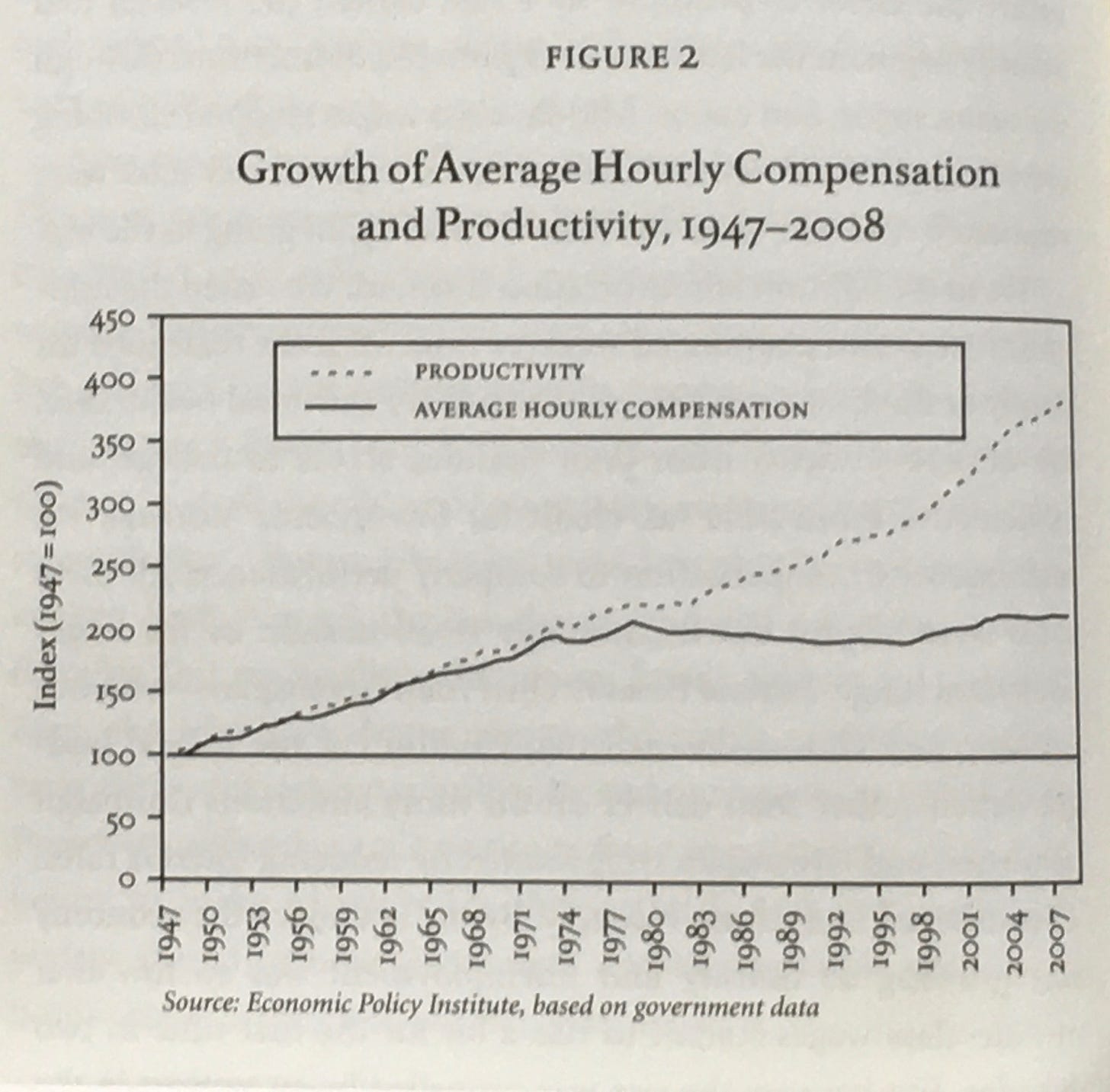

This basic bargain was the basis for three decades of shared prosperity after World War 2 (1947-1975, in Reich’s reckoning). When those lessons were forgotten, and that basic bargain was broken, the result was another economic calamity.

Drawing heavily on the work of Marriner Eccles, Reich argues that the Great Depression was a result of maldistribution of wealth. The income of workers did not rise in proportion to increases in productivity. The economy grew during the 1920s, but the new wealth was mostly directed toward the wealthy. This reduced the purchasing power of the rest, who had to borrow in order to maintain their spending. When they could borrow no more, consumption plummeted, causing businesses to fail, causing unemployment, further reducing consumption in a vicious downward spiral.

Reich notes three parallels between the lead-up to the Great Depression and the Great Recession.

The first parallel is income inequality.

The share of total income going to the richest 1 percent peaked in both 1928 and 2007. (p20)

A second parallel is increasing household debt.

In the years leading up to 2007, with the real wages of the middle class flat or dropping, the only way that they could keep on buying—raising their living standards in proportion to the nation’s growing output—was by going deep into debt. […] Savings had averaged 9-10 percent of after-tax income from the 1950s to the early 1980s, but by the mid-2000s were down to just 3 percent. The drop in savings had its mirror image in household debt (including mortgages), which rose from 55 percent of household income in the 1960s to an unsustainable 138 percent by 2007. Ominously, much of this debt was backed by the rising value of people’s homes.

The years leading up to the Great Depression. Between 1913 and 1928, the ratio of private credit to the total national economy nearly doubled. Total mortgage debt was almost three times higher in 1929 than in 1920. (p23)

A third parallel is speculative activity.

In both periods, richer Americans used their soaring incomes and access to credit to speculate in a limited range of assets. With so many dollars pursuing the same assets, values exploded. […] Yet […] expanding bubbles eventually burst. (p24)

Reich also notes the biggest difference between the two calamities. Government policies after the Great Depression led to a “new economic order”, with an expanded social safety net, protections for workers, and massive investment in infrastructure and human capital. But in the wake of the Crash of 2008, policymakers failed to grasp the need for fundamental reform.

Reich reviews the oligarchic and revanchist policies since the late 70s that brought us to this point, which I’ve already talked about in this newsletter and will probably talk about again in the future, and so I will pass over these for the time being and move on to Reich’s chapter 8, “How Americans Kept Buying Anyway: The Three Coping Mechanisms”, to wit:

Women move into paid work

Everyone works longer hours

We draw down savings and borrow to the hilt

It is easy to see how this dovetails with Warren’s work, especially #1 and #3. Concerning #2, Reich says that by the 2000s, “the typical American family put in 500 hours of additional paid work, a full twelve weeks more than it had in 1979” (p62).

In Part 2, “Backlash”, Reich prognosticates about the likely direction of politics from 2010-2020. Things haven’t panned out exactly the way he suggested they might, but he was broadly correct about the continued rise of resentment, anger, and populist demagoguery and its attendant threats to democratic institutions.

In Part 3, the “Bargain Restored”, Reich offers his policy proposals to restore the basic bargain.

A reverse income tax (expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit)

A carbon tax

Higher marginal tax rates on the wealthy

A reemployment system rather than an unemployment system

School vouchers based on family income

College loans linked to subsequent earnings

Medicare for all

Public goods (increased investment in publicly owned facilities, including infrastructure, parks & recreation, museums, and libraries)

Money out of politics

These are familiar prescriptions, so again, I won’t get into the details, but I will point out what he does not call for. Like Elizabeth Warren and unlike Juliet Schor, he fails to mention the need for reducing working hours. The omission is more disappointing coming from Reich, given what he says in chapter 8 (see above).

Overall, Reich does a good job of summarizing over a century of US political economy for the general reader and explaining its relevance for the present.

The fundamental problem is that Americans no longer have the purchasing power to buy what the US economy is capable of producing. The reason is that a larger and larger portion of total income has been going to the top. What’s broken is the basic bargain linking pay to production. The solution is to remake the bargain. (p75)